There are some bands that just hook me, as a writer. Often it has to do with lyrics, sometimes with the personalities involved. Tim Chan's band, China Syndrome, is one such group; I've been an enthusiast since the first time I saw them, and have written about them at least half a dozen times - including this (a review from 2015 of the first record of theirs I'd heard), this (their first feature in the Straight, done the next year), and this rather huge piece, also from the Straight, put online in 2018. Also talked to the Asian Persuasion All-Stars, featuring Chan, have interviewed him elsewhere on this blog, and dragged the great Bev Davies out to the Railway (the ORIGINAL Railway) to get this snap of Tim and Mike circa 2015:

China Syndrome at the Railway Club, by bev davies, not to be reused without permissionIn truth - like with the Pointed Sticks or Unleash the Archers or the Furies or a dozen other bands I've covered a lot - the amount of attention I've publicly paid China Syndrome probably gives a false impression of just how devoted a fan I am, but - also like with the Pointed Sticks or Unleash the Archers or the Furies - sometimes a writer just likes the people in a band, enjoys writing about them, and wants to do what he can to promote their music. And there ARE some fantastic songs in China Syndrome's catalogue, which have become part of my life. Erika and I have practically found an anthem in "Let's Stay at Home and Let It All Hang Out;" I'm a big fan of "My Pal Dan" and the darkest rocker in their catalogue, "One Too Many," both off The Usual Angst, which Tim just gave me on vinyl at that Railway show photographed above - and I definitely got a hook sunk deep in me with "Nowhere to Go," off their last album, Hide in Plain Sight, from 2018 (which feels like a weirdly long time ago, now, though you can still buy vinyl of it on the band's website). And Chan has an uncanny knack for finding great popsongs (often by Squeeze) and improving them with a cover...

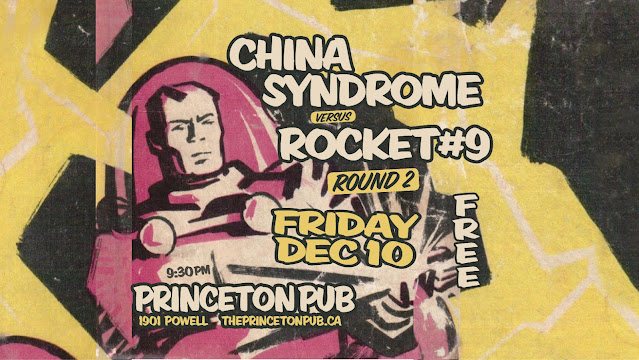

It's not looking like I'll be able to catch the band on Friday at the Princeton, with Ed Hurrell's new unit Rocket #9, but if you haven't seen China Syndrome, they're a very enjoyable, unpretentious, tuneful rock group with winning personalities that might just hook you, too.

So: here we go again - a Tim Chan interview for 2021!

What is the lineup of China Syndrome these days, and what's [former second guitarist] Vern Beamish up to? Is there a plan to get a fourth member? How much work was it to re-arrange songs to you being the only guitarist? (Was your experience in Pill Squad helpful?).The current lineup is the trio of myself, Mike Chang on bass, and Kevin Dubois on drums. Vern moved on just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit (good timing on his part) and is currently pursuing his own musical pursuits. I've been in touch with him a few times over the last little while, he's been hanging out with his wife Shona, playing classical guitar, doing some recording on his own, and adopting two new cats.

We are quite content being a three piece right now, and yes, we've needed to change our parts a little bit on some of our songs -- we've done some slight re-arrangements to songs like "Outta My Head" and "My Pal Dan," and have resurrected some songs from previous albums that we haven't played for a while. It's been hard work for me, though, as I've had to adapt some of my guitar parts to fill up the space where there used to be two and also play solos on songs where I didn't used to. It's good to be challenged, as my guitar style has always been riding that edge of being competent/ not competent, ha ha! For sure we are open to having a fourth member again at some point, and quite possibly it may not be another guitar player.

Are there any new tunes (or new cover tunes?) that you want to tell us about?We have a handful of new songs, but we have not been incredibly prolific with our writing over the past few years. You'd think the pandemic would free up some time for us, but it's been the opposite - our day jobs have kept us plenty busy. But we can't complain, at least we've remained employed! Our focus on rearranging existing songs and revisiting our older ones has also prevented us from learning new covers. We've been playing "2541" by Grant Hart for a few years now, along with Squeeze's "Pulling Mussels (from the Shell)" -- those are at least two that we will be playing at our gig on Friday. So no big surprises, unless you have a hankering to hear some China Syndrome deep cuts!

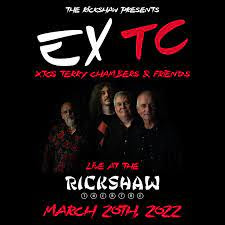

What have the musical high points of the last couple of COVID-years been, for you? Seems like at least some people took the opportunity to discover or rediscover bands they haven't done justice to - for me, it was Sparks and XTC. Anything like that for you? I too have gotten into Sparks during the pandemic. Was a casual listener until fairly recently -- really enjoyed the FFS album they did with Franz Ferdinand a few years ago, and I love their most recent album,

A Steady Drip, Drip, Drip! Other than them, I've been regularly listening to re-issues of one of my favourite quirky power pop bands from the 80s,

Game Theory - Scott Miller was one of the most brilliant writers ever, his chord progressions are incredible, not to mention his wonderful, oblique lyrics. I've also gotten into the Tuareg/ Niger artist

Mdou Moctar -- what a guitar player! Deep Sea Diver's album

Impossible Weight has been in rotation a lot over the past year - they're from Seattle. I've also inexplicably watched three Tom Petty documentaries in the past year, so I've been revisiting bits and pieces of his catalog as well -

Damn the Torpedoes is still my favourite by him.

Any standout moments from the Asian Persuasion All-Stars shows (all of which I missed?). Any interesting insights attained from participating in that project? (Will there be further live gigs?).Asian Persuasion All Stars have played two shows so far, our debut gig at LanaLou's in September and the opening event of the Vancouver Asian Film Festival at the swanky D6 Lounge in the Parq Casino in November - we shared the stage with the cast of the new

Kung Fu TV series, among others! It's been fun to be involved with my fellow Asian musicians (and supportive non-Asians) - there are 12 or 13 of us, so it's always good to bamboozle sound people, challenge them with the number of mics/ inputs that we need, and keep them guessing as to who the lead singer of a given song is! Anyways, I've really enjoyed getting to know the members of the group, having not played with many of them before. We've been lucky to get some

good media coverage for the band and our anti-racism message and I believe we have raised over $1,000 so far for Elimin8hate, the anti-racism advocacy arm of the Vancouver Asian Film Festival. And yes, we're keeping it going -- we'll be playing the Bowie Ball on January 8th, and then celebrating the Lunar Year of the Tiger with a gig at LanaLou's on January 29. We're also working on a new recording and video, so keep your eyes out for that as well. [See their cover of "

Racist Friend," here].

Any fun plans for Christmas? I assume you will be doing "Footsteps on the Roof" - anything else you care to share, special for the holidays?

Absolutely, we will be playing “Footsteps on the Roof” at the Princeton! We're still trying to establish that as a newish Christmas standard, like Wham's "Last Christmas," Mariah Carey's "All I Want for Christmas is You," and Paul McCartney's "Wonderful Christmastime"... don't understand what's preventing that from happening, ha ha! But what I am missing is the lack of No Fun/David M at Christmas shows this year!

I will go to visit my family in Victoria at Christmas for the first time in two years, so that's special! Otherwise, we will be pretty low key, Sarah and me don’t usually make a big deal about the holidays, our goal is always to try to keep it as low stress as possible.

The listing seemed to suggest that there was some sort of competitiveness between y'all and Rocket #9 - care to elaborate? (Do you have any noteworthy history with members of that band...?). No, the “battle” is just for fun, as this is the second straight show we’ve played with Rocket #9, so the fight theme just popped up in Scott Beadle’s gig graphic. Rocket #9 is fantastic — think Detroit hard rock like MC5, Alice Cooper, and Stooges! They were a hard act to follow the first time around and I’m sure they’ll be even better this time. A bunch of familiar faces in Rocket #9, it’s basically the Liquor Kings without EddyD — Steve Graf has taken on the lead vocals, with Mike Laviolette on rippin’ lead guitar, Terry Russell on drums, and Ed Hurrell on bass. Lots of connections — of course, I played with Ed in Pill Squad, and Steve played trumpet on “My Pal Dan” on China Syndrome’s 2015 album

The Usual Angst. We also did a bunch of gigs with them a while back when they played surf instrumentals as the Surf Messiahs.

China Syndrome and Rocket #9 square off this Friday at the Princeton; FB event listing here.