If you enjoy the following, note that there is a current interview with Art Bergmann in issue 94, which is not represented in this blogpost. Issue 94 is on the stands now (friends have found it at Indigo), featuring some terrific shots by Sharon Steele from Art's last appearances locally, at the Rickshaw in 2023, and out in White Rock a bit later (a concert I believe you can stream). It also (speaking of Alejandro Escovedo) has a feature-length interview with him (not done by me) and, relevant to nothing happening in Vancouver this weekend, the first of a two-part interview with Meat Puppets drummer Derrick Bostrom (that one is by me). Oh, and some of you might want to check out the cover story, too!

There's lots to update since 2017. Art has released two albums since. The one he talks about as a planned project, below, which at the time he thought he would call Entropy, came out as Late Stage Empire Dementia (the song "Entropy" is on it; to my mind, it's Art's finest moment this century). That was originally slated for release on Porterhouse Records, who did issue the song "Christo-Fascists" single, featuring the late Wayne Kramer, which you can stream here; there is also video here). But as we discuss in the 2024 conversation, plans for a retrospective compilation on Porterhouse got scuttled. Porterhouse did release some of Art's material around this time, including a gorgeous vinyl release of the Young Canadians Hawaii and digital versions of This is Your Life and the "Automan" 7", which you can find here. They also reissued a digital-only recap of the career of Los Popularos, more on which here.

Of course, we also talk about his relocation to Vancouver since the death of Sherri Decembrini, the recording of the album ShadowWalk, and plans for a new album, the recording of which is already underway. And Art does indulge a bit of digging into his back catalogue, most delightfully filling in a few few blanks about the writing of "Guns and Heroin," off the Poisoned EP. And we also talk about Art's plans for his next record, which is going to be a bit different; and about the atrocities in Gaza (his song "Gazacide" is online here; there's also a potent video for that, here. The video was assembled by Patricia Kay, "using all media from Palestinian creators").

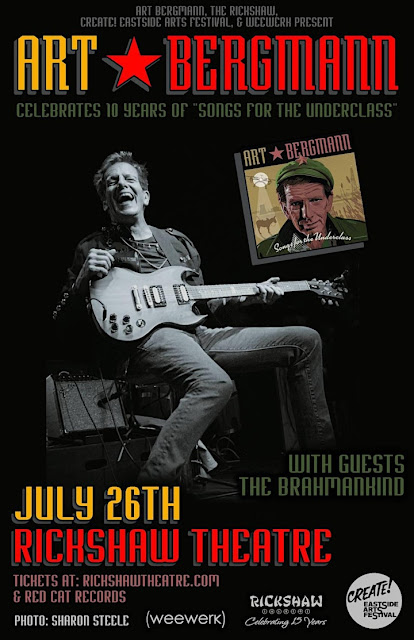

Let's go back to September 2017th, however. The Apostate had come out the year previously, the reissue of Remember Her Name was fresh, and we even spent some time on the album that is being released on vinyl for the first time, Songs From the Underclass, the 10th anniversary vinyl issue of which is the inspiration for the current show.

As the conversation began, I had just been watching Michael Glawogger’s final documentary, Untitled, completed after he died. As I explain in my original intro to the piece, "Art is a heavy reader and a fairly serious consumer of culture, and he’d asked me about the film - he asks YOU questions during an interview, sometimes - so we begin in a slightly unusual place."

Note: for the American version of this, I included several parenthetical remarks explaining some of the place names, but I've omitted them from this version, and tidied a few errors besides.

Art Bergmann by Sharon Steele, Rickshaw 2023, not to be reused without permission

AM: Have you seen any Glawogger?

AB: No, but - did he do the one about… well, who knows. I’ve seen so many documentaries that I don’t know how much more I can take. Why should I watch it? To slide further into my despair? What can I do about the situation? I can write a song, but fuck, no one listens to my fuckin’ shit! They never have.

AM: I think some people listen to your stuff.

AB: Yeah. I’ve had a big supply of 200 fans, all the time.

AM: Heh.

AB: We haven’t actually talked to each other before, have we?

AM: We’ve interacted a little bit. You came into a Rogers Video store in Maple Ridge where I was working in my 20s, with a couple of regular customers of mine, a man and a woman.

AB: In Maple Ridge? Was the woman named Katherine?

AM: I really don’t remember her name. But I asked you to sign a copy of Bruce McDonald’s Highway 61 [which Art acts in] on VHS, and you signed it, “Dear Al, Rent this sucker! - Art Bergmann.” Remember?

(somewhere in Maple Ridge there is a copy of this signed by Art Bergmann!)

AB: Uh, maybe. Where did you grow up?

AM: In Maple Ridge.

AB: Oh, wow - before it went crazy with overdevelopment?

AM: Yeah - I used to catch frogs and snakes there.

AB: It was part of the big northern wilderness there. I used to go up that highway all the time. I love it. I’d go up to Agassiz, Harrison. Beyond Harrison.

AM: You grow up in Surrey, right?

AB: Yeah - far east of Whalley and all that network. I grew up in Cloverdale/ White Rock. White Rock was quite an amazing town. There’s a reserve there, Semiahmoo Reserve. And there’s a bike gang called Gypsy Wheelers, who eventually joined Hell’s Angels. They were quite crazy individuals, but we used to play gigs for them! [Laughs]

AM: With John [Armstrong], in the Shits? [Supposedly so named, according to Armstrong, because people in the audience would yell at them, “You’re the shits!”]

AB: Well, we had a band before he knew how to play, even. The Mud Bay Blues Band people - we’d link up and play these weird biker gigs where, you know, if you got a biker putting his toe up and down, it was considered a success. They had cigarette packs full of cocaine that they dug their knives into. They were brutes, you know? Total brutes, the whole Hunter S. Thompson scene. We threw a gig once at our house out in South Surrey, and they showed up, and this one guy, man - the guy who hired me - he was threatening a woman, and then following an Indian friend that we had, chasing him through our yard. How do you deal with that shit? And for the first time, right, as a 16 year old…

AM: Wow.

AB: I was just learning how to play, how to write songs. And stupidly, glommed onto blues, learned how to play through blues and blues scales, playing in high school cover bands. We learned Led Zeppelin and Beatles and Kinks, who were my favourite. Listen to “Waterloo Sunset” - it changes every two phases, goes onto the next one. It’s an amazing pop song. But when you’re a white kid learning the blues, and putting on this chauvinistic fuckin’ machismo, it’s just pathetic; and that’s where my early songwriting comes from. So I don’t know what to say about it.

AM: You’re talking about the Shmorgs album? [Art’s vinyl debut, easily found in Vancouver record shops, revealing a pre-punk, Stonesy Art Bergmann].

AB: The Shmorgs album, some songs are okay, but limited, right? “Exhortation Rag” is my attempt at a 40’s swing tune. Living out in the far reaches of the Fraser Valley, I was in continuous despair, already, at seeing what people were doing with their lives. I had too many circles of friends who thought they had to get married and get a mortgage at 20. But Jim Cummins [I, Braineater] actually was a big supporter of mine, early on, and David Mitchell was the initiator. He was our singer, in the Mount Lehman Grease Band [another pre-historical Art Bergmann band].

AM: Where did that name come from?

AB: A grease band, well, that was joe Cocker’s band! I don’t know why they were called that. And Mt. Lehman was this forested area that these amazingly intelligent men had access to…

AM: How many shows did you even play?

AB: It was one year maybe, the end of high school graduation. The other guys went on, they played covers and blues. I separated myself from that. David Mitchell, unbelievably, went to SFU and wrote a bio of [British Columbia politician] W.A.C. Bennett and ran the Canadian Policy Institute out of Ottawa. Now he’s on his own, semi-retired. But he always liked his hedonism - made his way into politics because of it, I am sure. He was a shit disturber, but… whatever happened, happened. His parents were Montreal mob. My parents were Mennonites, and they ran a foster home. Somehow we ended up together in school in Abbotsford BC. But he ended being a Liberal supporter - that mafia. He turned up in a little show I did in Ottawa, a year and a half ago, so we met up again.

AM: What was your childhood like? Were you angry, happy?

AB: My childhood was extremely blissful and happy. My mother was very protective. I was a cruel child, like any other child is [Laughs]. But God, it was amazingly graceful.

AM: Were you parents interested in music? Did they disapprove of you picking up a guitar?

AB: No, they were extremely supportive of whatever I did. Later on, we got to play in the basement. My Dad helped us build a little studio, and my Mom listened with her ear to the floor. My Dad thought it was crap, because they were hymn people, off to the opera every Saturday, and they played Beethoven and big symphonies, classical music all the time. I was raised on that. Piano lessons, singing in church in German... But then my older brothers brought home rock’n’roll.

AM: What were the first bands you remember that really made an impression, that seemed like it was your music?

AB: Well - the first time I heard Elvis, or Buddy Holly, or Chuck Berry! It blows your world away; I was ten. And then the Beatles, of course. I totally swooned. And the Kinks, Stones - the Stones were a big one. I was a child of the 50’s and 60’s. In 1969, I went up to Squamish, Paradise Valley, for this festival, where every band got ripped off. But I saw Gram Parsons [with the Flying Burrito Brothers; Art sometimes still covers “Sin City”]. There was this crazy audience after Alice Cooper, and this most amazing light show, just blocks of light and feathers flying everywhere… Little Richard, who had a huge kind of onstage [wall?] with bikers in the front row, who were shrieking “n****r” at him - and oh, boy, he was so tough. Out of this world. I hitchhiked there, at age 15 or something, It was a life changing moment. These were the days when you hold the radio under your pillow and listen to late night shit comin’ from all over North America…

AM: Were there any Vancouver bands at the time that made an impression on you?

AB: Maybe a band called the Seeds [and here Art is referring to the Seeds of Time, not the Los Angeles band fronted by Sky Saxon]. They were really raunchy. The guitar player [Lindsay Mitchell] turned into a member of this awful band called Prism, but they had songs like “Mr. Dirty.” They were the same with the Stones and Zeppelin, with that faux machismo…

AM: And you were trying to write songs around that time?

AB: I still didn’t know how to write. I was just a follower. I really didn’t know how to start writing songs until I heard bands from New York in the 1970’s. John turned me onto the Dolls, Stooges, Iggy. And at first it seemed alien to me - I thought it had to be a bit more polished. And at 17, 18, 19, you don’t get the references to transsexual culture. I thought Exile on Main Street was it, you know?

AM: That’s what comes through for me with the Shmorgs, the Stones influences.

AB: Yeah, but with really weak lyrics. I needed an editor, all along. And a barber. I can’t even listen to it - I’m sorry. In photos, I look older at 19, working at sawmills and unloading boxcars, than I do now. There were two songs that were written with Jim Cummins, but they’re just empty of any meaning or emotion… Then John and Bill Scherk conspired to rip my world apart. John brought home a copy of a Sex Pistols cassette and it was amazing, we played that for weeks, months on end. It didn’t even feel alien - just so right, so perfect. Ah, man: no more self doubt or teenage angst or anything, you can fuckin’ say what you want and say it fuckin’ loud, and don’t worry about the engineer telling you to turn your amp down.

AM: It was the same for me, when I first heard it age 14 - really life-changing.

AB: You’re right. And by that point, I had been playing guitar constantly, so I really knew how to play. People in Vancouver were really amazed by it, because, from the word “go,” they were just learning their three chords. That was great, but I could add everything I knew into it, deconstruct everything I knew and add it into the mix, and that was the K-Tels.

AM: John makes it sounds like your Strat was something no one else could play, that it was quite a problematic instrument!

AB: Nobody wants these kind of details, do they, Allan? So what, that I could only play certain ways, on every fret I had to play a different kind of chord. It was quite unique…

AM: How did you connect with Bill [Scherk, AKA Bill Shirt, an openly gay vocalist who played with Art in the Shits, who became the Monitors, and later - after the Young Canadians broke up - sang in Los Popularos, with Art and John Armstrong]. If your childhood was anything like mine, there was a lot of homophobia around - outside Vancouver, if you looked at all different, you were called a “f****t” and beaten up. I know that you got jumped by gay bashers one night, too, and later you have songs like “Sexual Roulette” that speak to the AIDS crisis. So I wonder if you experimented with men, or if you were sympathetic to the queer scene?

Bill - Art - Zippy, of Los Popularos, by bev davies, not to be reused without permission

AB: Well - I was not antagonistic. I didn’t know anyone like that until I met Bill, and I loved Bill, we were in love with each other. And I experimented a lot around that time, 1976, 1977, but sexually it didn’t work for me; I tried [with men], and I basically couldn’t get it up physically. I moved on. But, you know - it was an enlightening period, the whole punk scene in Vancouver before the ridiculous restrictions of hardcore, y’know, the macho hardcore scene. The Vancouver scene before that was like the early New York scene. Every band was different: I remember seeing DOA, the Dishrags, and a band called Tim Ray and AV, and he had this really unique voice. It was a haunting voice, almost like Tom Verlaine’s, which at first sounds alien... That’s another band that blew me away, was Television. He was the greatest poet - Marquee Moon, I can still listen to it once a day. Tim Ray had that kind of voice, that sound - it’s haunted me since early 1977.

AM: There’s a Tim Ray CD that just came out, a compilation of his early stuff.

AB: Who put it out?

AM: Believe it was self released. It’s called History Lessons. He doesn’t get the respect he deserves.

AB: Well, he had a really singular voice. Because this yelling and spitting and stuff, you know - every band can do that, but do they have to do that? It’s silly. And the leather vest…

AM: Did you identify as a punk? You were on the punk scene, but did it feel like who you were, or were you just a musician?.

AB: No… I’ve never really been a musician!

AM: [Laughs].

AB: I’ve never identified with anything. The great thing about punk per se was that you could be exactly what you wanted to be, look like you wanted to look like, and everyone should look different. The earliest punks look liked nuclear survivors. Everyone was ripped up in a different way. You could go out and buy really cheap, amazing clothing. I went for sort of a degraded, elegant Edwardian kind of look - say a dilapidated kinda Kinks look. But you could wear whatever you wanted. There was no code. It was incredible. DIY, right? I remember going into a welfare office and they said, “you’re gonna need some clothes, buddy.” [Laughs] I had dayglo, man, and sharkskin pants and neon shoelaces and a wrecked Edwardian jacket, tryin’ to get some government money.

AM: Did you have a straight job?

AB: Nah. There was lots of construction, carpentry, labouring. You were always so strapped, but gigs seemed to come - in a bar, through a friend, through an acquaintance. You could get a job if you wanted one. I’ve done many labouring jobs.

AM: You never did the art school route, or university?

AB: No, I almost quit school just before graduation day, it was so fuckin’ awful. And I knew I wanted to rock and roll, from the age of 17. I took the vow of poverty. But if a job came up, I wouldn’t refuse it, no way. I’ve delivered postal parcels in vans with no brakes out in the Valley. I’ve loaded boxcars, worked at a sawmill. My last job was roofing, which was the most fucking difficult, back breaking fucking job you can do. But who can complain in this fucking world? I mean, we’re being destroyed by Trump taking over the news. They don’t play news from anywhere else in the world. I go to Al-Jazeera for my news. But that’s hard to take: I mean, floods and fires around the world, famine. Forty million kids are overfed while a hundred and forty million starve, I read that statistic today.

AM: It’s a dark world.

AB: And getting darker. In spite of all the evidence, we can’t seem to get our shit together. I just saw a great documentary on Chernobyl. There are wolves there, they’re thriving, beavers have come back, deer, bison. Every creature from the swamps that used to be alive in that area - Belarus and Northern Ukraine. It was quite amazing. Stalin had his labour force drain that place and cover it in concrete in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, and now it’s become a paradise, with scientists going in and measuring radiation - which has fallen quite precipitously among the creatures there. It’s beautiful, it’s amazing to see - a reminder of how much damage we do, man. We are the invasive species.

AM: It’s interesting that we are trying now to imagine how the world would look without us, how that seems kind of an ideal state. There’s even a book - The World Without Us.

AB: We’re in the athropocene era, right? Which is what the majority of scientists call it now, because we’ve laid down a layer of toxic shit deep enough that it will be found - like, an earlier layer of extinction.

AM: This is something that interests me about you, that there’s a real despair in your music, a darkness that comes in. But - like, it was really great to see you at the Rickshaw a few months ago, because it looked like you were having FUN, enjoying yourself, right? There’s a real joy, and there’s a lot of life in your music. But your view of human beings seems cynical and dark.

AB: I tend to take the long view, people just can’t see behind themselves, they don’t know history, they don’t know anything. But it’s good to stop being so irritable about the present and music and stuff. I just always wanted to be in a band, and nobody seemed to be doing it right. You know, I never wanted to be a leader or a loner, ever. I wanted to participate. Like in earlier times - hunter-gatherers in the forests of Mt. Lehman! [Laughs]. We used to beat on drums, have huge fires, climb trees, take a lot of acid… We laughed a lot. But you can't be in denial about what’s going on in the world. I mean, the USA - the whole phenomenon is just mind-boggling. The dumbing down - to think that education or government should be based on profit and loss, that’s fuckin’ bizarre to me. And if you read real history - people DIED for unions! My God. They would shoot and burn families in their tents, when they were on strike for some kind of equalization…

AM: Were your parents political? Did you grow up in a political environment?

AB: Oh yeah, I mean - we used to put together bulletins for my Dad’s union. He was a carpenter in CUPE, the Canadian Union of Public Employees. He worked maintenance for the school board out in Surrey, and became a secretary/ treasurer. I was six years old, holding up these bulletins for him, helping him out. That was part of my education. He was like a small-c communist, small-c Christian kinda guy [these words are echoed in Art's "Entropy," not recorded at the time of the conversation]. I wish I could believe in socialism…

AM: I often wonder about the title of The Apostate. For all the religious imagery in the album, I sort of relate it to the music industry. But I don’t know.

AB: It comes from the song “Mirage,” about fighting for human rights in a monolithic culture, wherever that might be. I got the idea for the song from a book called Death and the Dervish, by Meša Selimović, who was a dissident in Tito’s Yugoslavia, after 1945 and the Second World War, and his brother was executed for having a couch in his house which he had taken from a rich landlord’s house. And he set his story out in the monolithic Ottoman empire, which was so top heavy and top down that you couldn’t say a word against it. It’s about a Dervish who was a young priest in the Muslim system in the Ottoman empire, fighting against the system. It’s so poetically written, so well-written, it’s just amazing. “Feed the desert with the skulls of history” - it came off the page like a prayer, I thought it was a great idea. But an apostate is someone who questions anything remotely in the fundamentalist world, right? These mean fuckers will cut your head off, for that kind of thought, expressed vocally.

AM: Seems to me you read a lot of non-fiction?

AB: I’ve read a lot of fiction, too, but sad to say, my memory is not great, and I can’t remember the best bits of it. It’s sad - I should have kept a record maybe. But in the last couple of years I’ve read Miriam Toews and Heather O’Neill. But non-fiction - I’ve read lots of Marxist history, Howard Zinn’s book, uh… Marxist History of… uh…

AM: A People’s History of the United States of America.

AB: It’s fuckin’ amazing. All these rebellions that you’ve never heard about, slave rebellions, all these people rising up in previous times.

AM: I’m curious about “A Town Called Mean,” because - at the show, you dedicated that to Dashiell Hammett, and he seems to have had a pretty interesting life, including working for the Pinkerton detective agency, who if I remember were used as strike-breakers. And singing that “evil” has been good to you…

AB: It’s meant to be humorous, don’t you think? A killer being paid by a town to keep things in order… It was based on Hammett’s story “Nightmare Town,” which is about a town where everyone is so corrupt the guy can’t believe it, and he has to shoot his way out in the end. I don’t know if you know his work, but it’s unrelenting in its bleak criminality. I met a cop here [in rural Alberta, subject of Art's later "Amphetamine Alberta"] who said you could buy the whole city council for fifty grand. Which is a pretty bleak view of this town. The town is built on a low-lying area of swamp. There’s no real water - I don’t know where they get the water from. So you gotta know it’s based on real-estate corruption. And the whole rest of it - they build condos so small, one after the other, in the middle of agricultural land, and a beautiful kind of low-lying area for migratory birds on the other…

AB: It comes from the song “Mirage,” about fighting for human rights in a monolithic culture, wherever that might be. I got the idea for the song from a book called Death and the Dervish, by Meša Selimović, who was a dissident in Tito’s Yugoslavia, after 1945 and the Second World War, and his brother was executed for having a couch in his house which he had taken from a rich landlord’s house. And he set his story out in the monolithic Ottoman empire, which was so top heavy and top down that you couldn’t say a word against it. It’s about a Dervish who was a young priest in the Muslim system in the Ottoman empire, fighting against the system. It’s so poetically written, so well-written, it’s just amazing. “Feed the desert with the skulls of history” - it came off the page like a prayer, I thought it was a great idea. But an apostate is someone who questions anything remotely in the fundamentalist world, right? These mean fuckers will cut your head off, for that kind of thought, expressed vocally.

AM: Seems to me you read a lot of non-fiction?

AB: I’ve read a lot of fiction, too, but sad to say, my memory is not great, and I can’t remember the best bits of it. It’s sad - I should have kept a record maybe. But in the last couple of years I’ve read Miriam Toews and Heather O’Neill. But non-fiction - I’ve read lots of Marxist history, Howard Zinn’s book, uh… Marxist History of… uh…

AM: A People’s History of the United States of America.

AB: It’s fuckin’ amazing. All these rebellions that you’ve never heard about, slave rebellions, all these people rising up in previous times.

AM: I’m curious about “A Town Called Mean,” because - at the show, you dedicated that to Dashiell Hammett, and he seems to have had a pretty interesting life, including working for the Pinkerton detective agency, who if I remember were used as strike-breakers. And singing that “evil” has been good to you…

AB: It’s meant to be humorous, don’t you think? A killer being paid by a town to keep things in order… It was based on Hammett’s story “Nightmare Town,” which is about a town where everyone is so corrupt the guy can’t believe it, and he has to shoot his way out in the end. I don’t know if you know his work, but it’s unrelenting in its bleak criminality. I met a cop here [in rural Alberta, subject of Art's later "Amphetamine Alberta"] who said you could buy the whole city council for fifty grand. Which is a pretty bleak view of this town. The town is built on a low-lying area of swamp. There’s no real water - I don’t know where they get the water from. So you gotta know it’s based on real-estate corruption. And the whole rest of it - they build condos so small, one after the other, in the middle of agricultural land, and a beautiful kind of low-lying area for migratory birds on the other…

The K-Tels at the Cultch, with Jim Cummins painting ongoing behind them, by bev davies, not to be reused without permission

AM: If we could go back to talking about the K-Tels, how did you meet Jim and Barry? How did you start working with them?

AB: Well, my last with the gigs with the Shmorgs, in Vancouver, in 1977… Jim Bescott walked up to me afterwards and said, “you’re fucking great, man.” And we started playing together immediately, within a week or two. I had friends in the Shmorgs, long-time friends, but they couldn’t get modern, didn’t want to get modern with me. I said, “I’m going to town” [chuckles]. We started jamming, me and Jim, and auditioning drummers. It was amazing, the drummers who came around. One was Patrick [Steward], who is now a long-time member of the Odds. He got a gig right away somewhere else, but he had a friend named Barry Taylor, from up in Chilliwack, who was a very strange fellow. He had his hair blown off in some freak gasoline explosion accident on a farm. And he walked in and played like he was choppin’ up shit in a sushi bar. It was quite amazing - we said “let’s go, go with it.” We played our first show with four of five songs, the way it was done in those days; I think the Clash’s first set was twenty minutes. And people were blown away. These guys [Barry and Jim] were amazing musicians. I’m a pseudo-intellectual dilettante, I mean, but Jim was out of this world, you know? He had bipolar problems, and stuff, but it didn’t matter when we played together. We just clicked together. I was a fool to break the band up.

AM: You regretted that.

AB: Oh, for sure.

AM: When did you hear about Jim dying? It’s a terrible, terrible story.

AB: I still don’t know if he did it on purpose. Does anyone know?

AM: I don’t know. The way I’m told the story, he was with his Mom. That would be a hell of a thing to do to your Mom. It reads like an accident to me, but it’s so sad.

AB: It is sad, but… the truck was moving slowly through a parking lot. I dunno. It’s a thing that… I don’t know man… [portion indecipherable]. He threw a kick at me once, when I was walking down 4th Avenue. [He shouted] “Rock star!” and tried to kick me in the crotch. [Laughs]. I dunno. It’s sort of funny, but not.

AM: Were you in touch with him after the band broke up?

AB: Yeah, Barry and I were in touch regarding some royalties, when Jim was putting out some Young Canadians stuff. But no, we didn’t talk. That’s one of the reasons I broke up the band. We just couldn’t connect intellectually. Jim and Barry were completely different from each other, as well as different from me…

AM: Tell me about “I Hate Music.” That always blew me away, that you were so young and so cynical, to be singing that you hate music.

AB: We were fuckin’ damned with this bad clone boring ‘70’s shit, that was the deal with that song, right? I hated the fuckin’ assholes who kept putting this crap out, owned by the Bruce Allen mafia. And you had bands - fucking Trooper, fuckin’… I met Ray [Trooper’s Ra McGuire?] once: “You gotta compromise, you gotta compromise.” - “I’ll talk to you later, dude.” Y’know, then you get the first anti-corporate ideas of what punk is all about, to destroy everything and rebuild. Which is what it was all about, I thought. You get some cunt showin’ off on guitar like a cock… I mean, doesn’t that explain it?

AM:Yeah, it does… In terms of compromise with the record industry - the one album where It seems like you were listening to the marketing people a little bit is Crawl With Me.

AB: I wasn’t listening to anyone. I was - well, I can’t explain that total failure. I wasn’t into anything at the time. I was already three years into severe addiction at that point. I had this great demo done through Paul Hyde and Bob Rock. We had this deal with MCA Duke Street in Canada. They came up with John Cale, and - it was just a fuckin’ disaster from the word go, doing the same songs, because I didn’t have new ones. I had to go through severe withdrawl, but with money coming in to write a new album, called Sexual Roulette… but I hadn’t reached that point! And, y’know, John Cale wouldn’t let me play like I’d played with Bob and Paul, really guitar heavy and excited about it. He just stripped it all away. It was really - I didn’t know who to call or anything. I mean, when I went to mix it, I said, “you like guitar, don’t you?” It still didn’t help.

AM: It’s a sad album to hear. The record label fucked that up so badly.

AB: I let it happen. And it’s on me. [Art, leaving a comment on a past post here, has said, “the biggest mistake was not standing up for myself in studio situations, when you are being told by someone you formerly admired on what to do.”] But you know - I go across Canada, and people say they love it. I mean, they’ve never heard me before, so maybe that’s why. I couldn’t listen to it, I fuckin’ wept. Yeah.

AM: Sexual Roulette is a much stronger album - it’s much more you, but it’s on the same label; so what changed?

AB: I was playing in Toronto, and Duke Street suggested Chris Wardman, and he came to the show. He said, “oh, fuck, now I get what you’re all about.” In the live show, right? Which was more like Sexual Roulette in the sound and the attitude and the attack. And we had long conversations about what we wanted the record to sound like, I said I wanted it to sound like the band is trying to eat itself off the tape. I want the guitars really fuckin’ loud (chuckles) - as loud as everything else in the band, none of this bass-drum heavy keyboard crap. I mean, it took John Cale and one hundred and fifty grand to figure that out, and I wasn’t going to put up with listening to anyone, anywhere ever again.

AM: Do you have a favourite of your own solo albums?

AB: I like all three after Crawl With Me. The 1991 album with Polygram has a great bunch of songs. On What Fresh Hell is This?, “The Beatles in Hollywood” is really great (studio here, live 2023 here). I love the song “Dive” on that, too. I like them all equally. Sexual Roulette is right up there, except for some bits. “Deathwatch” is kind of an unfinished piece of scrap.

AM: Really? I like that one. There’s also a version of that on Vultura Freeway…

AB: Oh yeah. Freeway, there was another wasted effort. It didn’t sound as big as it could have had. I was enamoured with Prince’s keyboards at the time. I don’t know why - the fuckin’ onslaught of those keyboards in the 80’s…

AM (laughs): The songs still work. “Yellow Pages” is a great song.

AB: It’s one of those Todd Rundgren kind of songs. I don’t know why I went that direction after Los Popularos. I just had these songs and I wanted to record them, and I had three grand from working up in the seismic fields in Northern BC, so I just threw it into that.

AM: That was originally a demo cassette, right? The Poisoned cassette?

AB: That’s right.

AM: It could sound better, for sure, but I still like it. Coming back to Sexual Roulette, though, the song that fascinates me on that is “The Hospital Song.” I always wonder how autobiographical it is. I hope it isn’t - it’s a really painful song, your wife is in the hospital and her mother is lecturing you for what you’ve done…

AB: It’s true, yeah. That one’s true. (Sighs, falls silent). I mean… These days, I’ve been thinking, the plan was to die back then. But someone kept calling the ambulance… That’s a one liner. I’m good at one liners, but not at explaining myself.

AM: It’s a very sad song.

AB: Yeah, it is. She knew how to live, you know…

AM: I had always misunderstood that song. I kinda associated it with the violence in “My Empty House,” and assumed it was about wife-beating - that you’ve put her in the hospital with violence. But it was about drugs…

AB: You know, I never thought of that! I gotta be more careful. It was about drugs, an overdose situation.

AM: It’s somehow less scary knowing that. I was never much around really strong drugs, you know - cocaine, heroin. So I might be a bit naïve. I had friends who went that way and it did really bad things to them. I liked acid, back n my 20’s.

AB: I think [it’s valuable] to know of LSD. I think more people should take it, in this day and age, instead of methamphetamines - we have a huge epidemic here [in Alberta], as well as the opium/ fentanyl crap, which can kill you the first time. My God. But yeah, cocaine turned you into an instant liar, and heroin turned you into a liar and a thief, eventually.

Art Bergmann 2024, by either Patricia Kay or myself, examining a bootleg comp where he plays on a Braineater track

AM: You’re on something for your arthritis, right?

AB: Yeah, I’m on a pain patch.

AM: How is your arthritis, anyhow? When I saw you at the Rickshaw, you seemed fuckin’ strong, you were pulling people up onto the stage. You didn’t seem to be worried about pain.

AB: I wasn’t worried because maybe I knew I wouldn’t be doing that for that much longer! No, you know - I still get a huge surge of adrenalin somehow from playing live, and - all caution to the wind, you know? I don’t give a shit. I’m gonna be a heap of dust soon enough.

AM: Do you regret it the next day?

AB: Yeah, more or less… but no, I don’t regret playing live. I wish I could do it more.

AM: Something I had heard about that show was that you were going to quit performing electric, that it was going to be acoustic sets from now on.

AB: That was true, but… there’s so much involved in even doing one show, it just pisses me off. If I could play a few shows in a row, that would be great. But no one is that interested, and no one has got any money. I mean, I’ve been back at it for - for four years now? I keep on travelling around in a van that - it affects my hands, you know? And I can’t play solo - I don’t feel I can play well enough to pull it off. I don’t know what you need. Money? I don’t know.

AB: Yeah, I’m on a pain patch.

AM: How is your arthritis, anyhow? When I saw you at the Rickshaw, you seemed fuckin’ strong, you were pulling people up onto the stage. You didn’t seem to be worried about pain.

AB: I wasn’t worried because maybe I knew I wouldn’t be doing that for that much longer! No, you know - I still get a huge surge of adrenalin somehow from playing live, and - all caution to the wind, you know? I don’t give a shit. I’m gonna be a heap of dust soon enough.

AM: Do you regret it the next day?

AB: Yeah, more or less… but no, I don’t regret playing live. I wish I could do it more.

AM: Something I had heard about that show was that you were going to quit performing electric, that it was going to be acoustic sets from now on.

AB: That was true, but… there’s so much involved in even doing one show, it just pisses me off. If I could play a few shows in a row, that would be great. But no one is that interested, and no one has got any money. I mean, I’ve been back at it for - for four years now? I keep on travelling around in a van that - it affects my hands, you know? And I can’t play solo - I don’t feel I can play well enough to pull it off. I don’t know what you need. Money? I don’t know.

AM: Yeah. Actually, that reminds me - I wanted to ask about Design Flaw, with Chris Spedding.

AB: People love that record - a few people. I don’t know, that was just something to do in the meantime. It was nice for people to do it with me - Peter J. Moore, who did the Cowboy Junkies, and Chris Spedding, for him to play, that was great.

AM: I had wondered if having a second guitarist with you at that point was because the arthritis was starting to affect you?

AB: No, it wasn’t until after I moved out here. After the roofing job, really.

AM: Ah, okay. Well. So are these reissues and new albums making you any money, is it getting a bit easier out there?

AB: Not really. I get a few hundred dollars every three months from SOCAN for radio royalties here and there. I made a couple hundred bucks from “Atheist’s Prayer” playing on the CBC. And there’s a weird old song from Los Popularos that me and Bill [Scherk] wrote, where every three months, a few hundred bucks comes in from the USA. I’m not sure where it’s from. It’s really strange - it’s an unknown song, I don’t even know if we recorded it. I gotta ask Bill about it!

AM: What’s the name of the song?

AB: They write it down as “City’s Haunted.” I remember it being “This City is Haunted.”

AM: Never heard of it…!

AB: I’ll have to query Bill about that and make sure he’s getting his share.

AM: I’d wanted to ask about one other song on Sexual Roulette. “Dirge No. 1,” also, is a fascinatingly dark song. “The chicken blood ran in the gutters/ and man, did it stink:” I love the precision of that image. It always puts me on the north end of Commercial Drive, in Vancouver, by the chicken rendering plant that’s there, and the stink that comes off it on a summer day…

AB: It’s worse than that in the Kensington Market in Toronto. That’s where I was coming down from doing Crawl With Me and I had this insanely addicted friend who I stayed with through his wild ride. I was willing to detox - I was detoxing - but he was going on with his crazed coke life. I was amazingly clear-eyed, and watching this happen…

AM: There’s some racial violence in the song - there’s a line about the “disco of the ages” turning “a man into a racist”… Was racial tension something you saw a lot of in Toronto at the time?

AB: No, it was the music. Whatever the ethnicity of restaurants that were down in the market - Portuguese, Afro-whatever, they played the hits of the day. And they played disco forever ‘til four in the morning, and - if you’ve ever been in a live market, where they have live meat and fish and everything else, the smell got pretty intense.

AM: So the line about how he’s going out tonight “to kill every black man that I see,” was that coming out of hostility to disco, then?

AB: Yeah, that came from disco and the dealers he dealt with that the time. I guess it’s pretty racist! I don’t know why I said that, it’s pretty evil actually. But it’s not me, it’s me telling a story. I think I say “he” - “he says, ‘I’m going out tonight and kill every black man I see.’ ”

AM: It’s still shocking to hear.

AB: People love that record - a few people. I don’t know, that was just something to do in the meantime. It was nice for people to do it with me - Peter J. Moore, who did the Cowboy Junkies, and Chris Spedding, for him to play, that was great.

AM: I had wondered if having a second guitarist with you at that point was because the arthritis was starting to affect you?

AB: No, it wasn’t until after I moved out here. After the roofing job, really.

AM: Ah, okay. Well. So are these reissues and new albums making you any money, is it getting a bit easier out there?

AB: Not really. I get a few hundred dollars every three months from SOCAN for radio royalties here and there. I made a couple hundred bucks from “Atheist’s Prayer” playing on the CBC. And there’s a weird old song from Los Popularos that me and Bill [Scherk] wrote, where every three months, a few hundred bucks comes in from the USA. I’m not sure where it’s from. It’s really strange - it’s an unknown song, I don’t even know if we recorded it. I gotta ask Bill about it!

AM: What’s the name of the song?

AB: They write it down as “City’s Haunted.” I remember it being “This City is Haunted.”

AM: Never heard of it…!

AB: I’ll have to query Bill about that and make sure he’s getting his share.

AM: I’d wanted to ask about one other song on Sexual Roulette. “Dirge No. 1,” also, is a fascinatingly dark song. “The chicken blood ran in the gutters/ and man, did it stink:” I love the precision of that image. It always puts me on the north end of Commercial Drive, in Vancouver, by the chicken rendering plant that’s there, and the stink that comes off it on a summer day…

AB: It’s worse than that in the Kensington Market in Toronto. That’s where I was coming down from doing Crawl With Me and I had this insanely addicted friend who I stayed with through his wild ride. I was willing to detox - I was detoxing - but he was going on with his crazed coke life. I was amazingly clear-eyed, and watching this happen…

AM: There’s some racial violence in the song - there’s a line about the “disco of the ages” turning “a man into a racist”… Was racial tension something you saw a lot of in Toronto at the time?

AB: No, it was the music. Whatever the ethnicity of restaurants that were down in the market - Portuguese, Afro-whatever, they played the hits of the day. And they played disco forever ‘til four in the morning, and - if you’ve ever been in a live market, where they have live meat and fish and everything else, the smell got pretty intense.

AM: So the line about how he’s going out tonight “to kill every black man that I see,” was that coming out of hostility to disco, then?

AB: Yeah, that came from disco and the dealers he dealt with that the time. I guess it’s pretty racist! I don’t know why I said that, it’s pretty evil actually. But it’s not me, it’s me telling a story. I think I say “he” - “he says, ‘I’m going out tonight and kill every black man I see.’ ”

AM: It’s still shocking to hear.

AB: It’s like in “The Legend of Bobby Bird” - “another dead Indian.”

AM: Is that song based on fact, or…?

AB: It’s totally real. I couldn’t possibly make that up. I had to call the family and get their permission. And learn how to say their name; they said, “don’t use the word fuckin’ Cree, man, it’s a colonial construct.”

AM: Really, where does the word come from?

AB: It’s a lazy way to say Anishinaabe. Which I learned to say from his family. But there had been a story that got written in the Calgary Herald, written by a Saskatoon writer, called “Cold and Alone.” And it’s about how his bones were finally found, by a dogged family member and an old RCMP member, from 1969, when he ran away from res school outside of Saskatoon. He was ten years old, and the bones were found, with a white tailed deer bone, which was finally linked up with his family’s DNA through DNA technology in 1999. It took thirty years to identify that the bones were his. And there’s ten thousand of these kids, and I thought we could link them together in a song. But it’s a story of a brutal endeavour, right…? It’s amazing, what happened to these kids, torn away from their family at the age of five, six, seven, and you can’t speak your own tongue: they fuckin’ beat you. It’s a true story, basically.

AM: Yeah. I don’t know if you know about it - there’s this project that came out a couple years ago, putting together a compilation of First Nations musicians, people like Willie Thrasher, Gordon Dick, Morley Loon, some of whom lived through the residential school system, then went on to play in rock bands and such. There have been a few albums now - the Native North America series. No one really knew their music, but this Vancouver guy named Kevin James Howes has been compiling it and they’ve put out four albums now. Some of the songs are just amazing. Do you know this album?

AB: No, I don’t.

AM: I’ll make sure you hear it. Do you have a big First Nations community up there?

AB: Many, but I really don’t know how to approach them. I’ve been invited out to Saskatoon to play the Bobby Bird song for a monument they’re lifting, at the res school outside Saskatoon, but I’m not really in touch with anyone. I’m hoping to get in touch with someone who’s got cheap cigarettes!

AM: (Laughs) Are there other songs you’re proudest of on the new album?

AB: “Pioneers.” …You know - once I’ve finished a song, I hang onto them as long as I can, because once I’m done with them in the studio, it’s like - ah, I can’t hear them anymore. But a year later, I finally put The Apostate back on, and I told Lorrie [Matheson, the producer] “Pioneers” is a masterpiece. He’s responsible for the tension that goes all the way through the song.

AM: Is that based on anything specific in Canadian history?

AB: It’s based on a lot of things - it’s how the west was lost. Hey, did you know Peter Perrett of the Only Ones has released a new record? It’s called “How the West Was Won.” It’s a great song. But yeah - “Pioneers” is based on the brutalization of the west, industrial slaughter, a horde of cannibal killers. Ever read Blood Meridian, by Cormac McCarthy?

AM: Yeah, yeah!

AB: There’s a big fight in Halifax right now over a statue, what the fuck was his name? Cornwallis? He put out a bounty on the Mi’kmaq, all you had to do was bring in the scalp of any man woman or child. It’s kind of symbolic of the rape and torture of the west. [As of January 2018 the statue has been removed].

AM: I get a lot of my history from songs like this, you know? Like, there’s a song by a punk band here, the Rebel Spell, called “The Tsilhqot’in War,” about the killing of highway workers putting a road through Tsilhqot’in land (Wiki here).

AB: When did that happen?

AM: I don’t know. The 1860’s? But there was a small uprising, where four or five warriors killed highway workers, and before they were hanged - this is used in the chorus of the song - that they didn’t mean this as an act of murder. They meant it as an act of war.

AB: I’ve never heard of that, I’ll check it out.

AM: I’d also wanted to ask about a song on Songs for the Underclass. “Company Store.” It reads to me as a sort of homage to Bob Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm” - “you’re all whores at the company store.” I love that!

AB: Actually, I heard that on [CKUA radio?] up here - they played “Maggie’s Farm,” and then they played “Company Store” right after it.

AM: [Laughs]

AB: Yeah, he’s a big influence, Mr. Dylan, of course. My parents - the church had brought in draft dodgers, right, and we had a couple stay with us. And this one guy was a total Dylan freak. And one day he took acid and went through the whole Dylan discography. It was quite amazing. I’ve always been blown away by Mr. Dylan.

AM: Is that song based on fact, or…?

AB: It’s totally real. I couldn’t possibly make that up. I had to call the family and get their permission. And learn how to say their name; they said, “don’t use the word fuckin’ Cree, man, it’s a colonial construct.”

AM: Really, where does the word come from?

AB: It’s a lazy way to say Anishinaabe. Which I learned to say from his family. But there had been a story that got written in the Calgary Herald, written by a Saskatoon writer, called “Cold and Alone.” And it’s about how his bones were finally found, by a dogged family member and an old RCMP member, from 1969, when he ran away from res school outside of Saskatoon. He was ten years old, and the bones were found, with a white tailed deer bone, which was finally linked up with his family’s DNA through DNA technology in 1999. It took thirty years to identify that the bones were his. And there’s ten thousand of these kids, and I thought we could link them together in a song. But it’s a story of a brutal endeavour, right…? It’s amazing, what happened to these kids, torn away from their family at the age of five, six, seven, and you can’t speak your own tongue: they fuckin’ beat you. It’s a true story, basically.

AM: Yeah. I don’t know if you know about it - there’s this project that came out a couple years ago, putting together a compilation of First Nations musicians, people like Willie Thrasher, Gordon Dick, Morley Loon, some of whom lived through the residential school system, then went on to play in rock bands and such. There have been a few albums now - the Native North America series. No one really knew their music, but this Vancouver guy named Kevin James Howes has been compiling it and they’ve put out four albums now. Some of the songs are just amazing. Do you know this album?

AB: No, I don’t.

AM: I’ll make sure you hear it. Do you have a big First Nations community up there?

AB: Many, but I really don’t know how to approach them. I’ve been invited out to Saskatoon to play the Bobby Bird song for a monument they’re lifting, at the res school outside Saskatoon, but I’m not really in touch with anyone. I’m hoping to get in touch with someone who’s got cheap cigarettes!

AM: (Laughs) Are there other songs you’re proudest of on the new album?

AB: “Pioneers.” …You know - once I’ve finished a song, I hang onto them as long as I can, because once I’m done with them in the studio, it’s like - ah, I can’t hear them anymore. But a year later, I finally put The Apostate back on, and I told Lorrie [Matheson, the producer] “Pioneers” is a masterpiece. He’s responsible for the tension that goes all the way through the song.

AM: Is that based on anything specific in Canadian history?

AB: It’s based on a lot of things - it’s how the west was lost. Hey, did you know Peter Perrett of the Only Ones has released a new record? It’s called “How the West Was Won.” It’s a great song. But yeah - “Pioneers” is based on the brutalization of the west, industrial slaughter, a horde of cannibal killers. Ever read Blood Meridian, by Cormac McCarthy?

AM: Yeah, yeah!

AB: There’s a big fight in Halifax right now over a statue, what the fuck was his name? Cornwallis? He put out a bounty on the Mi’kmaq, all you had to do was bring in the scalp of any man woman or child. It’s kind of symbolic of the rape and torture of the west. [As of January 2018 the statue has been removed].

AM: I get a lot of my history from songs like this, you know? Like, there’s a song by a punk band here, the Rebel Spell, called “The Tsilhqot’in War,” about the killing of highway workers putting a road through Tsilhqot’in land (Wiki here).

AB: When did that happen?

AM: I don’t know. The 1860’s? But there was a small uprising, where four or five warriors killed highway workers, and before they were hanged - this is used in the chorus of the song - that they didn’t mean this as an act of murder. They meant it as an act of war.

AB: I’ve never heard of that, I’ll check it out.

AM: I’d also wanted to ask about a song on Songs for the Underclass. “Company Store.” It reads to me as a sort of homage to Bob Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm” - “you’re all whores at the company store.” I love that!

AB: Actually, I heard that on [CKUA radio?] up here - they played “Maggie’s Farm,” and then they played “Company Store” right after it.

AM: [Laughs]

AB: Yeah, he’s a big influence, Mr. Dylan, of course. My parents - the church had brought in draft dodgers, right, and we had a couple stay with us. And this one guy was a total Dylan freak. And one day he took acid and went through the whole Dylan discography. It was quite amazing. I’ve always been blown away by Mr. Dylan.

AM: I was wondering about Neil Young, too. I was really happy to hear you cover “Cortez the Killer.” And“Drones for Democracy” [also on Songs for the Underclass] sounds like it’s almost a Crazy Horse song.

AB: Yeah - after we played that song [“Cortez the Killer”] by accident, I went online and checked it out and found out that everyone and their dog were playing it. So I thought I would write my own song with that kind of vibe. The chorus [“what if you knew them”] is straight from “four dead in Ohio.” But I added the dreaded fourth chord…

AM: I know Bev Davies was friends with Neil - did you ever interact with him?

AB: How would she be friends with him? Just because she was a photographer?

AM: No, no - she knew him from Ontario, before he was famous. Bev has known some wild people, she was friends with Philip K. Dick, when he lived in Vancouver.

AB: You’re kidding. When did he live in Vancouver?

AM: He came up here to get off drugs, as I recall - do you know A Scanner Darkly?

AB: Totally.

AM: It was inspired by his experiences in Vancouver, detoxing or such. Some place called Ex-Kalay? He writes about it in Valis, too.

AB: That whole scene - was he part of the CIA program, testing LSD and that?

AM: I don’t know about that.

AB: You know about Ken Kesey, right? I thought I heard Dick might have volunteered for the acid program, like Ken Kesey did.

AM: I don’t really know. My understanding is, Dick didn’t like acid too much. He found it too frightening - he was more into pills and amphetamines or such.

AB: Have you seen the documentary on the speed-fueled Nazi army?

AM: No!

AB: No shit, they were fueled on methamphetamines. The whole population was fuckin’ on it - soldiers were writing letters home, begging for them to send it - it was over-the-counter. Pervitin, it was called. People thought they were like fuckin’ ants, they’d fuckin’ charge for six or seven days straight, if not longer. Isn’t it amazing? Look it up on Youtube - look up “Pervitin Nazi Army.”

AB: Yeah - after we played that song [“Cortez the Killer”] by accident, I went online and checked it out and found out that everyone and their dog were playing it. So I thought I would write my own song with that kind of vibe. The chorus [“what if you knew them”] is straight from “four dead in Ohio.” But I added the dreaded fourth chord…

AM: I know Bev Davies was friends with Neil - did you ever interact with him?

AB: How would she be friends with him? Just because she was a photographer?

AM: No, no - she knew him from Ontario, before he was famous. Bev has known some wild people, she was friends with Philip K. Dick, when he lived in Vancouver.

AB: You’re kidding. When did he live in Vancouver?

AM: He came up here to get off drugs, as I recall - do you know A Scanner Darkly?

AB: Totally.

AM: It was inspired by his experiences in Vancouver, detoxing or such. Some place called Ex-Kalay? He writes about it in Valis, too.

AB: That whole scene - was he part of the CIA program, testing LSD and that?

AM: I don’t know about that.

AB: You know about Ken Kesey, right? I thought I heard Dick might have volunteered for the acid program, like Ken Kesey did.

AM: I don’t really know. My understanding is, Dick didn’t like acid too much. He found it too frightening - he was more into pills and amphetamines or such.

AB: Have you seen the documentary on the speed-fueled Nazi army?

AM: No!

AB: No shit, they were fueled on methamphetamines. The whole population was fuckin’ on it - soldiers were writing letters home, begging for them to send it - it was over-the-counter. Pervitin, it was called. People thought they were like fuckin’ ants, they’d fuckin’ charge for six or seven days straight, if not longer. Isn’t it amazing? Look it up on Youtube - look up “Pervitin Nazi Army.”

Bob Rock, Art and Gerry Barad at Little Mountain Sound for recording of the This is Your Life EP Jan 1980, by bev davies, not to be reused without permission

AM: I will. I want to ask you about a couple of old songs. “No Escape” [about cops abusing punks in Vancouver] is my favourite Young Canadians song, and I was wondering if there was a particular episode with the cops that inspired it.

AB: When they tore into the Smiling Buddha, it was ridiculous. And tore up DOA - everybody who had been there. We all went to the cop shop, and we were all let out the next morning. It was pointless, it was stupid. We didn’t even know what we were charged with. Underage drinking? I don’t know. At least I got a song out of it.

AM: Ha! And then there’s the story about you and John [Armstrong, AKA Buck Cherry of the Modernettes] getting taken for a gay couple and getting bashed after a Mitch Ryder concert. John tells the story pretty well in Guilty of Everything, but I was curious if you had anything to add.

AB: It was after a Mitch Ryder concert, yeah. I don’t recall what John said about when the audience turned [as Armstrong tells it, Ryder, bisexual, was performing a blues song about a man-on-man sexual encounter in a bathroom stall, and the crowd - including a fair share of classic rock rednecks who had come for “Devil With a Blue Dress” - would have none of it]. I was pretty drunk by that point, so I don’t know about that part of it. But we were walking in the West End - we had gotten invited to a party somewhere - and they tried to run us over, screamed at us, “cocksuckers, fuck you.” And they tore around the block, came back and broke my jaw. It held up my thriving career by two months.

AM: Do you still have any issues with it? Does your jaw ever hurt?

AB: No, I just have a wire in my jaw.

AM: It’s weird, because, I’ve had that stuff like happen myself, not too long ago. These guys in a Camaro or something…

AB: That happened recently?

AM: It was maybe ten years ago. It was during the Gay Pride parade and - I mean, I just lived in the neighbourhood, and I was going to get breakfast or something, and these guys were yelling out the window, “Hey f****t.” I mean, I was just some guy on the sidewalk. But that shit is still around.

AB: Probably even more, now, with the unleashing of angry white people. So did you get hurt?

AM: No, they were just yelling at me out the window.

AB: It’s crazy.

AM: You look like someone who would fight back, though, from what I’ve seen of you. From what I’ve seen of you onstage - you look like a scrapper, I don’t know if that’s true.

AB: Oh, no - I’m a fuckin’ hippie child, man! [Art recalls a story about an encounter with a high school bully - a portion of the audio is untranscribable]. The guy came up to me and said, “fight me,” and I looked at him, this fuckin’ jocko homo monster, and I said, “No.” I got away with a split lip. But he would have fuckin’ tore me to pieces, right?

AM: We’re not that different, in that. So what are your favourite Young Canadians songs, from back in the old days? What do you think is the best song you wrote, back then?

AB: I don’t usually take stock like that, but, uh… I can’t even remember them all. But, “This Is Your Life"... You were asking in your email about “Hawaii,” and you’re right, Ross Carpenter wrote that song and I ripped him off! Believe it or not - he played it for me when I was almost in a blackout state, and I “wrote” it the next day, supposedly. I added a bridge… and no one pressured me on it for years and years. So I wrote him a letter, and asked him how it happened. He was an incredible engineer and recorder of his own stuff, and became part of Active Dog. But yeah, he wrote that song.

AM: Why didn’t you play that song for so long? It was maybe your most famous song, from the old days at least.

AB: I don’t know. I just thought it wasn’t the greatest song in my repertoire.

(The Porterhouse Hawaii package, I believe still available at most local stores -- possibly in black vinyl? -- complete with Art nude shot insert by bev davies)

AM: I don’t think it is either - “Data Redux,” “This is Your Life” “Don’t Bother Me” - these are all better songs. I even think the second EP, This Is Your Life, is the better of the two.

AB: Yeah. “Don’t Bother Me” is like an Elvis Costello-type disappointing love song. And I like Jim’s song, “Just a Loser.” I mean, we did these songs in Mushroom or Vancouver Studios with Bob Rock in a day. And I love the way they came off. But what is my favourite, though? Well… I like the stuff we were just getting into when we broke up. We had just been on tour with XTC, and I was just blown away by those guys. And I thought, “I can do better than what I’m doing now” - it was a definite throw down. Songs like the ones Zulu released from the last Young Canadians gig, “Picture of Health” and…

AM: “Poison of the Thought?” That’s the last song on the Zulu comp [now reissued by Sudden Death Records]. It says it was recorded December 13th, 1980, at your final show, at the Lotus Gardens.

AB: Yeah - I just reduced it to the word “Poison.” It’s a total Led Zeppelin-meets-the-Beatles song. I love it.

AM: The live Joyride at the Western Front CD, recorded in San Francisco, has some great stuff that never got a studio recording, too. “Beg Borrow or Steal” is fantastic. “Picture of Health” is on that too.

AB: Where did you find that?

AM: Bev gave me a copy, but - did it get released? I’ve never seen it anywhere except from Bev.

AB: I knew about it - I put it together with the guy, Keith Bollinger I think his name was, out of San Francisco.

AM: But, like, did it get distribution? I’ve never seen it in a store. You sounded surprised that I had it, and I know - like, there’s a Subhumans Canada album, Pissed Off… With Good Reason!, that came out on Virgin Records. It’s basically a CD comp with some live tracks, but it never got distributed, it’s basically a lost album. There are a few copies for sale online but Gerry Hannah told me it never actually got distro. [There are also copies of Joyride on the Western Front for sale online, note]

AB: I forget how he was going to distribute it, or anything else - it’s hard to say. It wasn’t that great a recording, in fact. But I know what being in that moment was like. There’s no reliving it.

AM: Since we’re talking about Bev - I wanted to ask about this photo that Bev took of you lying naked on the beach, for Hawaii, where your hands and feet are tied? Where did the idea for that photo come from? It’s really quite funny.

AB: It came from me - I was supposed to be in bondage in Vancouver! It was supposed to be the cover of Hawaii, but they [ie., Quintessence Records] wouldn’t do it. They were too scared of it.

AM: Bev told me she wouldn’t tie you up - she’d take the photo, but someone else had to tie you up.

AB (laughing): Yeah, Jim tied me up, I think. It’s a great photo - a fantastic idea, for that song “Hawaii,” or the idea of Hawaii, as coming out of Vancouver.

AM: I’m scanning through my questions here… [I had shown Art some questions ahead of time].

AB: Let’s talk about “Data Redux,” because I want to “reduce” that song to the level it should be left at. It was just a project I had one day: I had this heavy metal riff, which I thought really sucked and was derivative, and I wrote this song around it. It’s basically a fuckin’ spy novel, and who fuckin’ cares. And our manager at the time, Gerry Barad, who went on to become a zillionaire, with the Rolling Stones or whoever, said, “It’s a great fuckin’ song, you should record it.” It was just a little project where I reduced a spy novel into a song: “I met her at the embassy bar.” It’s total fiction.

AM: Was it based on a specific novel? Robert Ludlum?

AB: I never read Robert Ludlum. I’m a Le Carre man. And also I’m a huge reader of whatever comes up on the Cambridge Five - Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt, Donald McLean, Guy Burgess - who was an amazingly out-there gay guy, who just offended everyone in Washington. And there was a fifth guy… Do you know the story?

AM: Not really.

AB: These guys worked for the Soviets since the 1930’s. And Kim Philby rose up to be the head of fuckin’ British intelligence. Told the Soviets everything! And then went to Washington - and told them everything. It was amazing.

AM: I don’t read a lot of non-fiction, mostly I read novels.

AB: What kind of writers?

AM: I’m a big fan of Patricia Highsmith.

AB: I don’t know her.

AM: She was an alcoholic lesbian Texan who ended up living in Europe and writing novels about people with conflicted sexuality who end up murdering other people. The Talented Mr. Ripley was based on one of her books.

AB: Sort of bent murder mysteries?

AM: Very bent.

AB: Are they well-written?

AM: Very psychologically detailed. Graham Greene was a fan. She wrote Strangers on a Train, that was a Hitchcock film.

AB: Okay. I read all kinds of writers - German writers, French writers. All through Burroughs, and all that shit. And recently - whatever comes to my door. I like Miriam Toews. I love good writing, is all.

AM: Have you ever considered writing a memoir?

AB: No. I’ve got a compressed few lines - but I don’t know how to write, I’ve never thought of it. I couldn’t do it. I don’t want to do it. [Of course, since this time, a book about Art has been written!]

AB: It came from me - I was supposed to be in bondage in Vancouver! It was supposed to be the cover of Hawaii, but they [ie., Quintessence Records] wouldn’t do it. They were too scared of it.

AM: Bev told me she wouldn’t tie you up - she’d take the photo, but someone else had to tie you up.

AB (laughing): Yeah, Jim tied me up, I think. It’s a great photo - a fantastic idea, for that song “Hawaii,” or the idea of Hawaii, as coming out of Vancouver.

AM: I’m scanning through my questions here… [I had shown Art some questions ahead of time].

AB: Let’s talk about “Data Redux,” because I want to “reduce” that song to the level it should be left at. It was just a project I had one day: I had this heavy metal riff, which I thought really sucked and was derivative, and I wrote this song around it. It’s basically a fuckin’ spy novel, and who fuckin’ cares. And our manager at the time, Gerry Barad, who went on to become a zillionaire, with the Rolling Stones or whoever, said, “It’s a great fuckin’ song, you should record it.” It was just a little project where I reduced a spy novel into a song: “I met her at the embassy bar.” It’s total fiction.

AM: Was it based on a specific novel? Robert Ludlum?

AB: I never read Robert Ludlum. I’m a Le Carre man. And also I’m a huge reader of whatever comes up on the Cambridge Five - Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt, Donald McLean, Guy Burgess - who was an amazingly out-there gay guy, who just offended everyone in Washington. And there was a fifth guy… Do you know the story?

AM: Not really.

AB: These guys worked for the Soviets since the 1930’s. And Kim Philby rose up to be the head of fuckin’ British intelligence. Told the Soviets everything! And then went to Washington - and told them everything. It was amazing.

AM: I don’t read a lot of non-fiction, mostly I read novels.

AB: What kind of writers?

AM: I’m a big fan of Patricia Highsmith.

AB: I don’t know her.

AM: She was an alcoholic lesbian Texan who ended up living in Europe and writing novels about people with conflicted sexuality who end up murdering other people. The Talented Mr. Ripley was based on one of her books.

AB: Sort of bent murder mysteries?

AM: Very bent.

AB: Are they well-written?

AM: Very psychologically detailed. Graham Greene was a fan. She wrote Strangers on a Train, that was a Hitchcock film.

AB: Okay. I read all kinds of writers - German writers, French writers. All through Burroughs, and all that shit. And recently - whatever comes to my door. I like Miriam Toews. I love good writing, is all.

AM: Have you ever considered writing a memoir?

AB: No. I’ve got a compressed few lines - but I don’t know how to write, I’ve never thought of it. I couldn’t do it. I don’t want to do it. [Of course, since this time, a book about Art has been written!]

AM: Do you like Guilty of Everything? Do you see it as an accurate depiction of the time?

AB: John is an amazing writer. Really good, really great. He’s written four of five books in the last ten years. His book A Series of Dogs is really amazing - it’s about his life.

Jason Schneider, Aaron Chapman, and Art Bergmann at The Longest Suicide book launch, by Sharon Steele, not to be reused without permission

AM: He really admires you, as well. But… to return to the rock’n’roll questions, I know they’re kind of boring, but… there’s a story in the liner notes to Joyride about you pissing on the Boomtown Rats. What was that about?

AB: [Laughs] I climbed up on the grid-iron of the Edmonton Coliseum and I proceeded to piss on them!

AM: What was the problem with them? How did they treat you guys?

AB: They ignored us. They were on the rock’n’roll road to oblivion, they were a pile of shite. They couldn’t play their guitars, by the way. And I mean - where they now?

AM: So touring with XTC was a better experience?

AB: XTC refused to come and hang out with us - but they’re not that type of people. They were just phenomenal players. It’s nothing to cut them down about. The Boomtown Rats had this pseudo-kinda-rockstar thing happening. What was their hit?

AM: “I Don’t Like Mondays.”

AB: They were worse than the Shmorgs!

Art Bergmann, 2023, by Sharon Steele, not to be reused without permission

Art Bergmann plays the Rickshaw, Friday, July 26th! Tickets here, see you there.

No comments:

Post a Comment