Alan Zweig in Records, 2021

Alan Zweig in Vinyl, 2000

Note: the following piece was written in last minute in the face of impending surgery, and substantially revised once I had gotten out.

It's a great question, and opens doors onto issues of the pathology of collectors that any collector will walk away from pondering. It isn't always a comfortable experience, however. For example, Zweig interviews a fellow whose apartment is a squalid jumble of disorganized records and CDs, seen below. The subject gets defensive, angrily justifying his apparent hoarding with explanations about his testicle cancer, and lashing out at Zweig a bit, seeing Zweig as criticizing him. Zweig, actually, is just asking questions, and you could see bravery in his willingness to go there, but the segment still brings to mind documentaries like Shirley Clarke's Portrait of Jason or Terry Zwigoff's Crumb - all films which enter bravely into some pretty emotionally uncomfortable territory. (You might also be reminded of the cinema of Henry Jaglom, a bit). It's brave cinema, honest cinema, and has an emotional impact that most documentaries generally don't even attempt to achieve (which is pretty remarkable, really, given that it's a film about record collecting, which you might expect to be kind of fluffy, trivial thing; it is anything but).

Records is a much easier, gentler, more "fun" film about record collecting. As Zweig himself says in the film, if Vinyl is about failure, Records is about "acceptance."

That doesn't mean there aren't still a few fearless and revealing questions put in front of his subjects, many of whom, this time out, are couples, like Cindy Wolfe, the Tennessee Twin (left, below) and her partner, Toronto filmmaker Reg Harkema. Often Zweig is curious about whether his film's couples keep their collections separate or merge them together, and asks at least one couple (I'm forgetting who) if the decision to merge or not to merge their collections is a potentially ominous sign in terms of the couples' faith in their relationship. I don't know if Zweig himself thinks of that sort of question as brave, but as someone who has done a share of interviews, I probably would be really nervous about asking it, fearing that, fair question or not, my subject might take offense: "How dare you question whether my relationship is on solid ground?"

But Zweig is in a different relationship to the subjects of this film than to the subjects of Vinyl; they're successful peers, for the most part, and of a generally higher socioeconomic strata than the people depicted in the earlier movie. As with Vinyl, there are deep emotional insights attained into exploring people's relationships with their stuff, but the overall picture is not of lonely single people with no lives, engaged in compensatory or pathologicial hoarding. You get to see just how much people - including people in relationships - get from their collections. You even get to hear a few really fun bits of music (the bit about bellydancing record will stay with you, but I don't want to spoil it).

Conversation between Zweig and I began on Facebook, with a bit of back-and-forth about how the film's few Zoom interviews (with Jello Biafra, for example, glimpsed above) merge pretty well with the rest of his movie. I said something about liking the "charming lack of tech flare" of the film, referring in particular to how, for Zweig's own on-screen appearances, he uses the rather unpretentious (but nicely composed) shots of himself talking into a mirror, in the later film visibly shooting from a mounted iPhone. It's such a great idea - because where, in real life, does one talk to oneself, if not in a mirror? - that is made all the better for its humble means, and in fact looks great (Zweig's compositions are slightly altered for the images here, note, so I could crop out the runtime counter at the bottom of the screen!).

Zweig responded, "Well the mirror idea comes from Vinyl, but back then I had this huge mirror, this time I went to Value Village and found that one and it seemed perfect. I'm not sure my producer or DOP would like what you call 'lack of tech flare,' but I think I know what you mean, there's Zoom, there's old bits of Vinyl which was shot in hi-8 and there's the mirror stuff shot with my phone... and I like that too... It's not that I want anyone to like the film for that reason, but I would hate to think that anyone dislikes the film for that reason, though over the years I have met people who didn't like my films for their lack of conventional flourishes."

After that, we switched to Zoom.

Just to make it explicit. I love your aesthetic, I love the sense that these are just real people talking, with as little artifice between them as possible. I hope I didn't offend you with my thing about lack of tech flare.

No, okay - I mean, yeah... It's not something I exactly chose, but I did become aware at some point that it was different, and at that point, it was like, I saw no reason to change it. Although some of my films are slicker or prettier, if the subject matter calls for it - I can be less rough.

See, I don't know the films you made between - but you've seen things like Shirley Jackson's Portrait of Jason, and you've watched a lot of cinema. It's not an un-studied aesthetic.

Yeah. When I made Vinyl, I didn't think about it, but if I did think about it, I thought, "It's not the only documentary ever made that looks like this." The thing is, documentary has conventions, and documentary filmmakers have an attraction to those conventions more than I would expect filmmakers to be attracted to them. Documentary filmmakers, or the industry, is somewhat conservative. And that's why I started hearing a lot that my stuff was different. I feel like, in fiction filmmaking, there is quite a bit more of a range of aesthetics; there are auteurs with their own with their own style. Nobody is telling Harmony Korine every time, "Your films are weird." I would say my aesthetic is not so much what I do, as what I don't do. Like, I don't do B-roll unless the B-roll naturally flows from the subject. But I don't go out of my way. It's like, what was I going to do with people I was interviewing about vinyl, cut away to a dance sequence, or to them walking through the park, just for the hell of it, so we don't have to watch them talk in front of their records? I see no reason not to stay on the person who is talking. But people notice that - people notice the lack of B-roll. But anyway, we don't have to make a meal of that.

Okay. I see that there are some friends of mine in the film, who have Vancouver ties. I mean, not super close, but I know Reg Harkema, who shot some of his first film, A Girl Is a Girl, was shot in part at Neptoon Records, and Kevin James Howes.

It's funny - I just wrote Kevin and not said, "Just a warning, not everything you and Dane said ended up on the cutting room floor, and - it's going to Vancouver, and maybe some of your friends are going to see you.

And yeah, Reg is from Vancouver; I expect his father, Bill, to come to the screening. Reg and I are friends. Kevin and I are friends, but not hangout friends. But Reg and I have a history.

It's an interesting behind-the-scenes connection with Vinyl, because Reg has worked with Don McKellar on a few projects.

Reg and Cindy went to the Blinding Light on a date, to see Vinyl. And I've met a lot of people from Vancouver who saw Vinyl at the Blinding Light. I never made it there, but it was one of the sweetest gifts I ever got was that Vinyl became a hit at this underground cinema, and the only reason it happened was that the recently departed Dave Barber, from Winnipeg, recommended it to all kinds of people, including whoever was programming the Blinding Light. I know that Vinyl has a connection to Vancouver, for sure.

I volunteered at the Blinding Light for awhile - I saw a John Porter presentation there, and a few other fun films, and one gruelling film about Guy DeBord. I learned how to use a popcorn machine, too... I am guessing it was probably Alex MacKenzie who programmed it.

Alex MacKenzie, yeah.

Vancouver vinyl enthusiasts Dane Gordan Joulet and Kevin James Howes

Coming to something that is important to both films. If you had asked me, before I saw Vinyl or Records, about my record collecting, I would have said "well, it's really about the music for me." And one of the startling and funny things about both films is that it seems like people are in a bit of denial towards their orientation towards the artefacts. Like, they have 83 records by a given artist, multiple copies of it, and say they're not a collector. Or they have 10,000 records, and say they're not a collector. Or there's the guy who talks about having to buy every single album by an artist he likes who, in the next breath, says, "But I'm not a completist." What do you make of this? Is it denial?

And I didn't expect that to come up again here. The whole point of this film was kind of that on Vinyl, I got sort of sidetracked on the "It's not the music" thing, to the point that I wouldn't really even let in music. The film - Vinyl - is kind of about music, but it's kind of not at all. And I was like, "I'm going to make it again, and this time I am going to try to talk about music." And I think I did talk about music, this time, but I didn't think that that whole sawhorse, "I collect for the music" - I didn't think anybody would still say that. And then bang, they're saying it again. Like, "They're pulling me back!" (mimes Al Pacino in The Godfather III).

I think it's basically like this: if you have records all around your house, and it's not for the music, you're a hoarder. If you have records all over your house and it is for the music, you're an art lover, an art collector, you're a man or woman of good taste who collects fine objects of art. And I say, well, it's like the guy in the film says when he gets an attack of Parkinson's: "I go to the room, I pull out a record, and go, 'I have this.'" Does he put it on? No - he doesn't say, "I put it on and the music cures me." He thinks about the music; he imagines the music; and he might not have that record if not for the music on it. But... y'know. like, what does somebody who collects stamps say? What does somebody say - "I don't do it for this..." "I collect comic books; I do it for the stories." Like, of course you do, but I'm just saying...

Right, yeah, you're right, and I don't want to make it about quibbling, but - and this is kind of boring, but I will say it, anyway. Most of us, like you and me, are not technically record collectors, because a collector in every other thing involves getting a complete set. Like, say he collects Bowie; he has all the pressings. He has the Italian pressing. Maybe he has Mick Ronson or Tony Visconti records, too. That's a collector. If you're like us, we blow with the wind: "I've got a couple of Bowie records, but why would I need a hundred?" I've got ten Dylan records, or, you see in the film where I'm like, "I've got six Mike Nesmith records, and that's too many, I don't like him enough to have six records." So we're not record collectors, technically speaking. But I asked somebody once, way back in Vinyl, "Okay, what should we call ourselves, then?" He said, "Accumulators." And I tried to introduce that into the language, but it didn't stick. They're collectors and we're collectors, but they're real collectors, and we're, y'know, "vinyl enthusiasts," or something like that.

But you're right, there's a lot of knowledge about records that might not constitute music. You just talked about Reg. Reg knows about the dead wax, Reg knows about who cut the lathe. There's a term people use this term "Pork Ears" [?] or - I can't remember what they use, but those people who know who cut the lathe will say it's because the music sounds so much better when this guy cut the lathe, versus that guy. And they would definitely say, about all this information they have, "Yes, I'm aware of all that, but it's because I want my music to sound better." There's nobody who would say, "It's not about the music." Nobody.

And the thing is - it's not important. It's funny that people have a feeling that collecting is frowned upon, so they want to separate themselves from those people; I might have felt that way too, back when I made Vinyl. But I don't feel that way now. I think, if you have thousands of records, and you listen to music, and you love rummaging, and it makes you happy - good for you. You're lucky! You found something that makes you feel happy. You don't have to hide behind false distinctions.

|

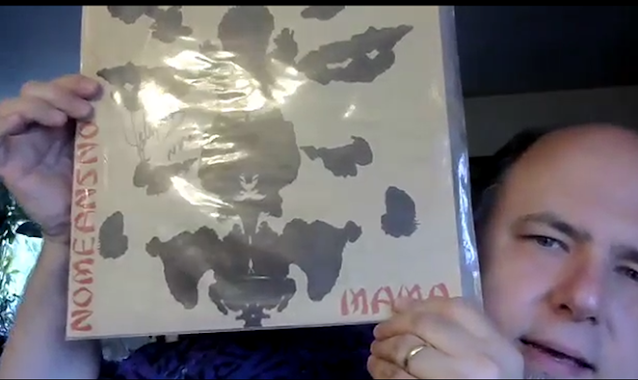

To me, that's too much - it's too artefact-oriented. I grant that yes, it's going to protect the record cover from wear a little, in the long term, but it just bugs me to imply that, you know, we shouldn't use the cover of the record like the cover of the record. Even with this one, I store it inside the sleeve, where it belongs.

I am not precious at all about my records. I don't even have them in plastic sleeves, because I don't like how they look on the shelves. I throw the plastic sleeves out. I'm shocked to find out that I'm a way small minority in throwing out plastic sleeves! But I am not trying to preserve my records for the future, or so that I can sell them for a lot. When I sell them to stores, sometimes I get ten bucks, sometimes I get five bucks, but... I'm not a condition freak. In fact, let me show you. I'll show you what kind of collector I am. Here's one example (holds up Andy Robinson album): somebody cut holes in it, and put things in them, apparently, I'm guessing, so they could put their album covers in a binder and go through them. [Imitates flipping pages]. Somebody else would not buy this record from this, but I would buy it because of this.

(Laughs). Okay.

And I'm going to give you one more example: Neil Young, Everybody Knows This is Nowhere. I already have it. I used to love this record - when this came out, I played the shit out of it. I probably haven't played it a few times in the last ten years. Anyway, I had to buy this copy, because the people were so bold in putting their names on it. Like, I like when people put their names on it, but - obviously, these guys even had stencils. I would even consider, as a fantasy, of trying to find Gloria and Dave Lemon and being like, "Hey, I got your Neil Young record!"

So on the topic of Neil Young, then. I didn't understand a scene in the film, where you're speaking into the mirror and you have the back covers of four Neil Young albums on view, not the front covers. Why did you do that?

Um. [Thoughtful pause]. Because I thought that if somebody objected to my showing Neil Young records, or wanted money, they would be less inclined to do so if I showed the back. How many people would know that?

Okay, well, I'll tag him in this, or something. But if I could ask - I have a favourite moment in Records, where your daughter teases you about the size of some of your audiences, theatrically. That's charming. It was spontaneous, not scripted at all?

No, I wouldn't script that. I mean, I've told her many things about my life, and when my film, A Hard Name, played at the Royal in 2009 - going back to my films I made in the 1980's and 1990's, I would be happy to get twenty people, ten people. But I particularly remember A Hard Name, when four people or six people would show up. And the weird thing is that you're actually very grateful to those five people, because all it would take would be for five people to decide not to go out that night, and you would have had zero people. And I've never had zero people, but I've been five people away from zero people!

But she busts my balls, that's what you're saying, and yeah, she does; every once in awhile, my daughter says something, and I stupidly say, "How'd you get so sarcastic?" And she's like, y'know, "The apple doesn't fall far from the tree."

You have a family? A wife?

I had a wife. Keely has a mother; she and I were together for nine years. We split up when Keely was about six, which was about five years ago. I met somebody two years later, and now I live with my girlfriend, and I have my daughter, all this time, three and a half days a week.

It's something I noticed was absent from the film. Not a flaw, but you talk about other people's collections, do they merge their collections and such, but you don't really go into your family situation that much. Do you share music with Keely?

No, not really. I know people do this, and people have told me they do this, sitting their daughter down and playing them stuff. I couldn't imagine doing that with her. I don't do that with people, period: "You've gotta listen to this!" So no. Occasionally she'll hear me playing things, but I'll let her come to it or not come to it. I have introduced her to movies, maybe, or some TV stuff, but mostly we watch and listen to stuff that she knows, like "Call Me Maybe" by Carly-Rae Whatever. Like, one time her and her mother heard a song on a Turtles record that they thought was hilarious, and they used to do imitations of it, and it is really quite a weird song. But the kind of stuff I listen to, I don't really impose it on anybody, and I don't really even impose it on my girlfriend. I play music for her, but I am careful not to play her music that I don't think she'll like, because she has very good taste, but quite different taste from me; our tastes intersect here or there. But, y'know, one time I was listening to Rotary Connection. They made a bunch of very weird, conceptual psychedelic soul records. They're semi- half-black half-white records; Minnie Ripperton was their singer. And I thought - my general tastes, she's not going to like, but she might like this; they were covering the song "The Weight" by the Band, and they were covering it in the kind of way, like they do, that would seem, almost, you couldn't tell that it was that song until they go "take a load off Annie." And she told me, "I've never liked this song. I didn't like the original. Too male, the Band. Too male."

I do have stuff that she likes, but I have two rooms where I listen to my music: Downstairs, where I put all the stuff I can play for my daughter or girlfriend or at a dinner party, like Van Morrison, Jackie de Shannon, et cetera, and upstairs, where I have the 60's swampy/ psychy stuff that I don't expect anybody else to like, and I listen to it by myself.

Relationships seem to be a huge part of the film. You've said it's about acceptance, and we've talked about collectors who are in denial, but the moment, to me, the one that really stood out was the single woman in her 60's who says, "I suck at relationships, too; they take me away from my stuff." And that's a really profound moment, that tension between relationships and your stuff. It's the first time I've seen anyone go into it - I guess Philip K. Dick touches on it a little with the "your house is on fire, what do you save: your family or your books" thing. It's kind of the same paradigm.

When I made Vinyl, I think I made it very clear, in this film, that I thought somebody who didn't have relationships, didn't have a family, only had their records - which also describes me at the time! - was missing something, and maybe even was a bit of a loser. Now, I didn't make fun of them, but I had some pretty extreme examples of those kinds of people, who found me, came to me, and they were kind of examples of cautionary tales. And it wasn't totally on purpose: the guy whose wife left him and took all his records, the guy who had memorized the K-Tel records, the guy whose record I stepped on; those were just people I met who I put in the film, but they ended up being part of a theme, which was my judgment - and I wasn't the only one who had that judgment - that you're missing something; that it's better if you have these other things in your life, and that your records should find a more reasonable level.

Now, I kind of knew I didn't believe that anymore, but I didn't know how much I didn't believe that anymore until someone brought up this guy Imants. I could see the old me judging him, and the present me going, "That guy was one of the happiest people I ever met!" And the thing that Margaret, who you mention, says - she's in Vinyl, a little bit, too, and I'm proud of her for saying it, rather than 25 years ago, going, "Well, good for you, but you're wrong! Now I think otherwise, and here's how I think I arrived at that: I'm extremely happy and grateful that I have my daughter, but having her, I realize it was a choice I made, to say, "I won't be happy unless I have a daughter." It was a choice I made, and I could have made another choice. I could have chosen to be happy in a different way. As much as she's the best thing in my life, I also realize that was a choice. [When I made Vinyl, I was like,] "Here are the things I have, here are the things I don't have, and I'm going to focus on the things I don't have and be miserable." And y'know, I just profoundly don't feel that way anymore, and that's why there's nobody in the film that I'm judging, and don't want anybody else to judge. I'm not going after anybody, I'm not nailing anybody. I'm glad they found something that makes them happy.

You wouldn't have been able to do that if you hadn't had a daughter.

That's true. I couldn't have. But it's not just my daughter. The thing about this film was, Vinyl was an earth shattering thing for me, personally; it changed my life. And I think it's a very self-indulgent choice I made, to make this film Records, as an homage to that film, which was earth shattering for me. Vinyl changed my life. I became a filmmaker. I got an audience. I became somebody that people would support. So that, and my daughter: two things I didn't have when I started to make Vinyl, which made me happier, and kept me happier to this day. But you're right, I had to get them to get the insight to realize that it was a choice. Whereas these other people, like Margaret, they've made their choice, and they're better people than me.

[Note: This is not a photo of Margaret, just a screengrab of a very well adjusted family whose partners both collect]

Thanks, Alan. One final question, just a very basic one. You don't use name cards at any point in the film. I'm curious about that. I didn't recognize Reg and Cindy at all, at first, since it's 14 years or so since I hung out with them, and, I mean, I only know what Steve Albini looks like from old Big Black album covers from 30 years ago, so I still am not sure who he was in the film.

That's just been something I haven't done since the beginning. One reason is that I don't want to identify every Tom, Dick and Harry, just so you'll know that's Steve Albini when he comes up; and if you have a few famous people, and they're kind of recognized, then the audience will also wonder if Dan Lovranski is a famous person they've never heard of. And then there's the fact that I don't really want to put too much focus on the famous people. And lastly it's because I consider my films to be collective stories, a bunch of people with similar issues and experiences, and I don't want to focus on any one of them too much. And finally, if I haven't already said finally, it's because I associate putting names under subjects with educational films or films trying to prove a point or argue something and they have to let you know that this is so and so from the oceanographic society. I know I have suffered from not putting the names and frustrated some people, but I just could not let myself do it, It's something that I would never do. it feels wrong and I don't need a reason, but I also don't want anyone going "Ooh, that's Steve Albini."

No comments:

Post a Comment