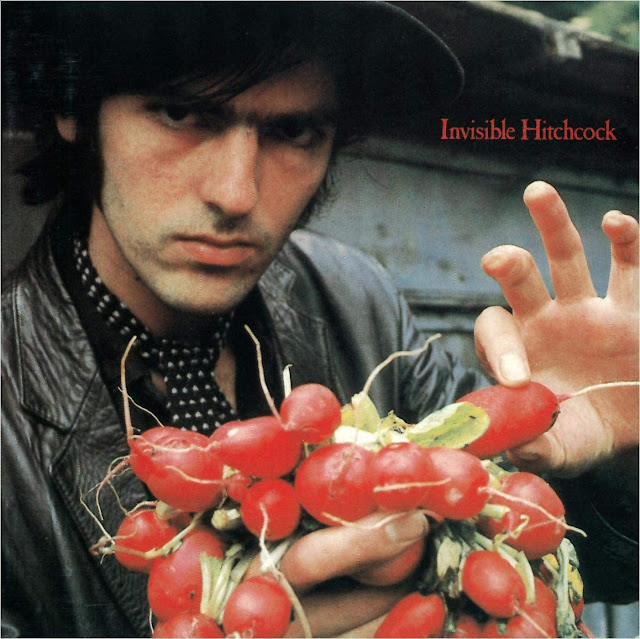

I've been listening a lot to Robyn Hitchcock lately, while I still wait for Shufflemania! to land in Vancouver shops (which I wrote a bit previously about here). I nabbed Invisible Hitchcock the other day at Red Cat, in fact, on CD, because I'd never seen it on CD before and because there were four bonus tracks on it, all of which I probably have somewhere else but perhaps not in the same version, who knows? ("Eaten By Her Own Dinner," I think, is the best known, and very Soft-Boys-esque, enough so that it's a slightly weird fit for this record, in fact, but what the heck). The LP of this was the first Robyn Hitchcock I ever purchased, probably getting it when it was brand new at Odyssey Imports, circa 1986, when I was 18. As such, I have quite a bit of attachment to it; there are some very fun songs on it, some very catchy ones, some very pretty ones. And even the cover speaks of Robyn's weirdness: why is he holding that radish and looking at you like that? It was one of my best blind or near-blind buys ever, perhaps fueled by my having read about Hitchcock in an early issue of Spin, but perhaps simply because I had to know what kind of music went with a photograph like this. I think that first version I had was the US pressing with "Grooving on an Inner Plane" on it; since I sold off my record collection when I moved to Japan, then re-acquired it, I ended up with the Glass Fish UK version, with "It's a Mystic Trip" - the better song, really, though both are fun. It always amazed me that the album is basically a collection of outtakes, demos, and non-LP tracks, because it's just so cohesive - can something be "consistently eclectic?" - and enjoyable to listen to; if I were assembling a Desert Island Hitchcock collection, this would be in the top 5 must-keeps, beating out such worthies as Element of Light (which the Glass Fish CD represents on the Invisible Hitchcock disc as the title of the album, for some reason) and Fegmania! and... well, lots of other Hitchcocks that I love less.

And yet, as well as I know this album, having purchased in now three times in three different versions, having to listened to many songs off it as repped in the While Thatcher Mauled Britain anthology, it still yields secrets. Because I knew nothing of the Soft Boys' anthology Invisible Hits at the time I bought this record, it never occurred to me until YESTERDAY (26 years late, basically) that the title is punning on the other record's title, in the spirit of Groovy Decay, Groovy Decoy, and Gravy Deco (an example of a Hitchcock I don't even have or want - I had the Decoy version for a short time and sold it, deciding it wasn't bad but that I just didn't care; it has very little of what I'm interested in in Robyn Hitchcock's music, is more of a straight pop album. I see that one track on one version of it, "Falling Leaves," is now back in my home on my new Invisible Hitchcock CD).

Which brings us back to "The Sir Tommy Shovell," previously written about in that aforelinked blogpiece. Robyn's love of witty wordplay is evident at least from the days of the live side of the 1981 release Two Halves for the Price of One, Lope at the Hive (recorded live at the Hope, get it? It's a venue I do not know, but which is also namechecked on Invisible Hitchcock, rhyming with "dope" in the withering put-down "Trash"). Despite being long aware of Hitchcock's propensities here, I didn't put it together that "Shovell" might be a pun on "Shuffle," since I was distracted by trying to figure out if there was anyone who actually has that name. It also occurred to me, in listening to the song for the dozenth - is dozenth really a word? - time that the lyrics might be more complex and subtle than Hitchcock merely crafting a fantasy pub, where one finds like-minded individuals, good beer, vegan food, and none of those "racist losers" he pokes at at the end. He might actually be subverting his fantasy a little, in that he sings about wanting to find people who "agree with everything you say/ every single day," which immediately reminds one of the echo-chamber effect we get on social media: if people disagree with you, if they have different ideas or values, it's become somehow socially appropriate to belittle them, insult them, craft ad-hominem arguments, misrepresent their views, and/or block them from further interacting with you. Maybe there's some slight commentary on that, and on the tendency to demonize your opponents (calling them a racist is certainly a popular way, these days).

Anyhow, that song has been on my mind, while other songs - "The Feathery Serpent God," which has resonated against my recent Graham Hancock binge and the restrained, bluesy near-rocker "The Midnight Tram to Nowhere" - have risen in prominence since I first heard them (that latter has a stellar bit of wordplay in it, involving a recontextualization of the cliche that "it takes all kinds of people," but I'll let you discover what he does with that for yourself.) The climactic track on the album, "One Day (It's Being Scheduled)" also has some uncharacteristically (but apparently sincere) heart-on-sleeve, emotive writing in it, but I haven't really come to terms with it yet, so... The album continues to grow on me, as does Queen Elvis, which is by no means a recent album, but which I've been happily re-exploring, since it contains plenty of mysteries that I have not yet unravelled and gave me a nice Hitchcock to trade off listenings of Shufflemania! with (I've also been re-exploring Eye, which I like much better than when it first came out). ...

But sticking with Queen Elvis, a lyric on a song off it really hit me in an unusual way the other day: "Freeze." It would be folly, perhaps, to take any of Robyn Hitchcock's lyrics too personally - as I say in that other piece, he seldom asserts a value with undermining or at least complicating it - but, as people who follow this blog (or my Facebook posts) know, I had a tongue surgery last year that left me with a speech impediment and problems swallowing, which means that sometimes I have excess saliva in my mouth. So there I am, walking to Metrotown Skytrain, Queen Elvis on my headphones, and I encounter THIS lyric:

I know who wrote the book of love

It was an idiot

It was a fool

A slobbering fool with a speech defect and a shaking hand

And he wrote my name

Next to yours

But it should have been David Byrne or somebody

Hey, wait a second there, Robyn! I'll leave the issue of whether I'm a fool or not open - I mean, maybe, but jeez, just because someone is slobbering and has a speech defect, it doesn't mean that they're an idiot! Ableism! Ableism!

It gave me a moment's pause, but mostly amused me, to discover a lyric that would have blown by unobserved and unremarked-upon in any of my PREVIOUS 53 years, but now in my 54th is suddenly kinda fraught.

It's true, you know, we judge people, especially their intellect, by the sound of their voice. Come to them with a stammer, a slurp, a lisp, a cleft palate, or just some goofy-sounding, imprecise mumbling, and you will likely be deemed mentally deficient in some way, until you prove otherwise. I used to do it, too, never thinking to question it. It's been a surprising discovery!

I didn't write the fuckin' book of love, either, there, Robyn. It ain't me, babe.

I do wish Shufflemania! would hurry up and get here, but then again, I can't really afford to buy it right now anyhow, and I can hear the whole thing online, so...