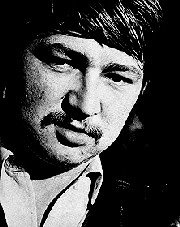

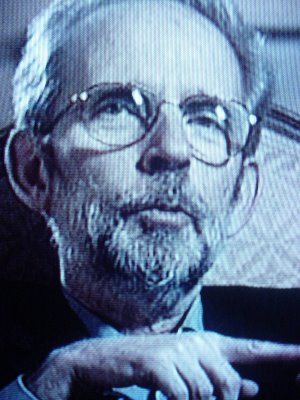

Film editor and sound designer

Walter Murch spoke at the Vancouver International Film Centre, also known as the

Vancity Theatre, last night, giving one of several sold out talks to a crowd largely consisting of young filmmakers from

SFU’s Praxis Centre for Screenwriters. After his introduction, we watched

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation – my favourite of the films he’s worked on, though he is perhaps better known for participation in films like

THX 1138, Apocalypse Now, The English Patient, and

Cold Mountain, and for his work on the posthumous “director’s cut” of Orson Welles’

Touch of Evil – many of which he discusses with Michael Ondaatje in the book

The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film.(Murch has also written

In The Blink of an Eye , which discusses his work in greater depth). The evening was a most engaging consideration of the crafts of both editing and sound design, and I think everyone left feeling quiet respect and fondness for Mr. Murch. For those who couldn't be there, here's a rough recounting of events.

Murch has a fine speaking voice – a deep, rich baritone; and he has the gift of being able to describe subjects ordinarily regarded as somewhat arcane in a fascinating, accessible way, in part due to his facility with metaphors. Anyone unfamiliar with him is invited to explore this article on sound mixing (“Dense Clarity, Clear Density”)

here, linked off

Filmsound.org’s archive of Murch articles. Since last night’s event, like all of Murch’s Vancouver engagements, sold out shortly after tickets went on sale, I had to sit for two hours on the cold concrete outside the box office in hope of a cancellation; I was first in a long line, and, along with a young actor and Vancouver Film School TA named Dean and an unidentified SFU film student who bitched about the cold an awful lot (but had interesting things to say about the reception of

Jarhead), one of three people who were let in at the last minute. (I have seldom had such enjoyable conversations while waiting in a line up with strangers; cinephiles all, we discussed our disappointments with Terence Malick’s

The New World, the upcoming screening of a new print of Cassavetes’

Love Streams, and recent exciting Criterion titles, from

The Bad Sleep Well to

Bad Timing; Dean had the enthusiasm of a true believer, and, coming from Alberta, lacked the Vancouver reticence about talking with strangers; I suspect those who didn’t interact with us directly greatly enjoyed eavesdropping on our conversation).

Murch introduced

The Conversation by relating that people often comment that “they don’t make films like that anymore,” telling us that he usually replied by saying, “‘They didn’t make films like that then, either…’ Francis had been nursing the project since the 1960’s, and it was only after the success of the first

Godfather film – the film was made between

The Godfather I and II – that Paramount grudgingly agreed to produce it.” Murch detailed the production problems of the film; the original DOP, Haskell Wexler, quit and was replaced by Bill Butler; the film went overbudget; and, because Coppola was committed to beginning preproduction on the

Godfather II at a fixed date, also went over schedule; there were 15 pages of screenplay – 10 days of material – that they didn’t get a chance to shoot. Francis told him, “Well, Walter, I don’t know – there’s all this unshot material. I think the best thing to do is to cut it all together and see how big the holes are.” Murch shrugged. “There I was with all this footage, and I thought, ‘Well, okay.’”

It was to be Murch’s first feature film; he was to edit it on a

KEM Flatbed, a piece of editing technology that was relatively new to American cinema and quite unlike the industry standard Moviola. If I got the anecdote correct, Coppola had brought the Flatbed over from Europe, and

The Conversation was the first American film to actually employ it. On top of all this, Murch was trying to edit a film that wasn’t, in fact, complete. (The audience laughed warmly at Murch’s dry delivery; he conveyed his sense of haplessness quite well, though he later explained that in fact being a beginner was probably an asset for him, since he had no previous feature work to compare the experience to). At the start of the shoot, “Watergate was a tiny blip on the horizon – nobody expected it would lead to Nixon’s resignation.” “Sadly,” he concluded, “the film is still very relevant today.”

On seeing it again for the first time in years,

The Conversation reminded me, to my surprise, of David Mamet’s

Homicide. As in

Homicide, a character with a bad conscience becomes morally involved in a situation he doesn’t fully understand, making assumptions about what is happening that are more informed by his own guilt than by a clear perception of events. (The following telling of the film will contain mild spoilers). Gene Hackman, as Harry Caul, gives one of his best performances, as a careful, privacy-obsessed Catholic wiretapper (violating the unofficial film rule that all Catholic voyeurs must be played by Harvey Keitel) whose previous work led to a murder, for which he is trying to escape a feeling of responsibility; he was modelled – as Murch also explains in

The Conversations – on

Steppenwolf’s Harry Haller, and the film conceived of as “a cross between Herman Hesse and Hitchcock,” though the character study supersedes the mystery. As with Brian DePalma’s

Blow Out (Murch would later explain), the film was intended as an “audio version” of Antonioni’s

Blow Up, a vastly influential film (actually my least favourite of Antonioni’s) in which a photographer believes he has captured a murder; as with both of those films, everything hinges on the character’s ultimate failure to make a difference in the world he perceives – which can be read as a figuring of the ultimate failure of the audience to intercede in the events it observes on screen, a theme that sometimes crops up in self-reflexive cinema.

Watching the film last night, I was compelled for the first time to wonder about the film’s politics. Caul, at the beginning of the film, believes that he is “just doing his job;” he vociferously denies any responsibility for the moral effects of his work, though his lingering guilt suggests that in his heart he knows better. In hindsight, at the end of the film, it could be argued that he in fact would have been wisest to maintain his distance from the events. Is the film subtly trying to argue against “getting involved,” telling people that they had best not meddle in corporate politics, not to “get in over their heads” in matters they know little about? It seems like a possible reading -- the apathy that stems from hopelessness could be seen as validated by the events of the movie -- but this perhaps doesn’t do justice to the complexity of the film’s final images. When last we see Caul, his cherished privacy permanently lost due to his involvement in the job, there is the sense that he actually has been liberated; he appears to have finally given up his attempts to maintain control of his circumstances, which, given how obsessive and paranoid he has been previously, might just be good for him. The paradoxical liberation he undergoes complicates attempts to read the film as reactionary, as does the ultimately depressing effect the film has on its audience; if a weight has been lifted from Harry’s shoulders, it has been placed squarely on ours, since we leave the theatre feeling both vaguely compromised (having ourselves misunderstood what was going on, alongside Caul) and even more mistrustful of corporate politics than we were on going in.

The most satisfying image in the film for me is that of a hotel toilet, clogged with rags after a murder has taken place, overflowing with blood. Toilets should always overflow with blood: it’s actually an image of great (if unsubtle) poetry, in which shit, guilt, shame, and death all merge together as one. Nothing suggests a universe gone wrong like a bloody toilet.

After the film, Murch returned to the front of the auditorium for a Q&A. I had a question that I have nursed for years about the film, never suspecting that I would actually be able to ask the man, and was the first to put up my hand. (Here the spoilers become terminal, and you are advised to stop reading and see the film before proceeding). The success of the film hinges on one line. Caul has recorded a young couple, played by Frederic Forrest and Cindy Williams, discussing their presumed infidelity; they say, at one point, of the man who is paying Caul to record them, “He’d kill us if he got the chance.” The line is given a flat reading, one that you hear fifteen or more times throughout the film, as Caul replays the tape, again and again; he believes he is about to become complicit in a murder, and delays in giving the tape to the director of the corporation who has paid him to make it. Since the film keeps us very close to Caul’s perspective, when the murder finally takes place (with Caul eavesdropping from the hotel room next door), we believe that it is the husband killing the wife. The film has a surprise for us: it is, in fact, the director of the corporation who has been murdered, killed by Forrest and Williams as part of a corporate takeover, the actual machinations of which are somewhat obscure. We hear the tape played one final time, and now, given our new understanding of things, hear it differently. Instead of hearing, “He’d KILL us if he got the chance,” the normal reading of such a line, which suggests it is the couple who have something to be afraid of, we hear, “HE’D kill US if he got the chance” – contrastive stress being cleverly used to imply, “So WE should kill HIM first.”

Clever, right? The first time you see the film, you honestly believe, for a few seconds, anyhow, that you’ve heard the line differently, given your recent experiences; you’ve been taught a lesson in how unreliable perception is. In fact, all you’ve learned is how unreliable film editors are. Perception has nothing to do with it: Murch has played a trick on us, a very clever one, but which, for me, caused me briefly to reject the film. The second recording of the line is different from the first, places stress on different words. This was my question to Murch: what was the history of the cheat? Was it conceived of at the screenplay stage, or added in later?

(My scribbled notes are as complete as scribbled notes can be, but I should note that occasionally I am resorting to paraphrase in my attempt to transcribe Murch’s answer, below):

“The intention was for there to be no alteration at all, for the film to be an anti-

Rashomon; the key to the film would be that the meaning would change because you knew different things as the story progressed. We found, once we’d finished, though, that audiences had a hard time figuring out what had happened… It was one of the premises of the film that we didn’t want to specify everything. What were the exact relationships between these characters? We presume that Cindy Williams is Robert Duvall’s wife, but she could be his daughter. Is Harrison Ford the mastermind? We don’t know, because Francis didn’t know; he felt that if we knew, the pressure to get rid of the character study and focus on the murder mystery would be overwhelming, so we put…” Murch hesitated. “What do you call those things you put in the ground, in VietNam, that you… Uh…”

After no one else said anything, I offered, “

punji sticks.”

Murch nodded. “We put these punji sticks in the story to prevent this from happening.” (This is the one metaphor drawn by Murch in the evening that left me completely puzzled). “You only know what he knows, so we couldn’t do a Perry Mason at the end explain everything that’s gone on. We tried all sorts of things to get the idea across; we added material to the screenplay, and near the end of the process we’d screen it for 10 to 15 people at a time, nothing like these big preview screenings nowadays, and tried to find different ways to do it, but in the end no one really understood what had happened.”

“Well. I was mixing the film – Francis was in New York shooting

The Godfather II – and I remembered a reading where Frederic had put emphasis on a different word.” Murch explained that during the Union Square scenes in San Francisco – the opening crowd shots, where the recording of the couple takes place – it was next to impossible to get a decent audio track of everything; after six days of shooting, Murch couldn’t assemble a complete version of their conversation. He took Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest aside and, walking alone with them with a Nagra tape recorder, recorded a “

wild track” in which the two said their lines. “In the end, we had a fifty/fifty mix of the actual location recording and the wild track. The giveaway, that you’re hearing the wild track and not the location shoot, is that occasionally you’ll hear killdeer in the background… On take two, Frederic spontaneously came up with an alternate reading, and at the time, I said, no, that’s the wrong inflection, and we did it again. Well, there I was, mixing it alone, and I thought, why don’t I put in that reading? Maybe it will tip people that these are the perpetrators. It was risky; it violated the principles of the film, but I took it to New York and I prepared Francis for it, saying ‘I’ve done this thing with the inflection,’ and he liked it… That’s why it happens to be the way it is. In a way, it’s a case of the exception proving the rule; it’s almost because it violates the principle that we could get away with it.”

Other questions during the Q&A took us to areas covered in the Ondaatje

Conversations; what scenes were not in the screenplay? The dream sequence, for one; it was never intended to be a dream sequence, but the “connective tissue” that would have allowed it to be incorporated into the narrative wasn’t there, so the only way to include it was as a dream. The murder scenes, too, weren’t actually part of the script, but were filmed by Francis with no clear how idea how they would fit, and merged into the film as an “editorial improvisation that emerged out of the peculiarities of the film.” Much was also cut from the film, including a complicated subplot in which Caul turns out to be the owner of the building he lives in, which he is not repairing, since he hopes to profit from an urban renewal project in the neighbourhood; when the other tenants get upset about the lack of repairs, they elect Caul, not knowing he actually owns the building, to represent them, in a scene which featured Abe Vigoda. (Somehow mention of Abe Vigoda was sufficient to get a titter from the audience; those of you who are curious may wish to note that there is a

Firefox extension that will automatically inform you of Vigoda’s alive or dead status – he is, as of this writing, still alive; there is also a spoof of “Bela Lugosi’s Dead,” with modified lyrics to refer to Vigoda,

available for download - we assume this is all meant fondly). In the end, only one scene required that new material be shot: Meredith’s theft of the tapes.

“When he collects his money, in the original, he’s actually bringing the tapes. Meredith stealing them was actually a plot invention after the fact, done with editorial jiu-jitsu; initially, in the screenplay she was an agent of Moran, and she was there to steal the rolled up plans that you see Harry with. When you see Caul saying, ‘bitch,’ as it was shot, that’s what he’s discovered she’s stolen. We decided to bring the business with Meredith closer to the heart of the matter, but it required one extra shot, of Harry discovering the tape cases empty… In Los Angeles, we made a set of the tape recorder and the background. We were on a soundstage where Roman Polanski was shooting

Chinatown, also a Paramount picture, and Polanski was a friend of Francis’. We asked to borrow his camera, and he said okay; we got Gene Hackman’s brother, who was a stuntman, to stand in, and that’s his shoulder you see. If you panned to the side, you’d see Jack Nicholson, with the cut nose, and Roman waiting impatiently to get their camera back.”

Murch continued with the Q&A for a good half an hour after this, giving elaborate, well-spoken, and most illuminating answers, to questions which were uniformly well-considered. Asked about it, he told us there is nothing about the film that he now would change in hindsight, regardless of what new technology makes possible, and he disagrees with the decisions to meddle with

Star Wars, THX 1138, and, indeed,

Apocalypse Now, though he was involved in

Apocalypse Now Redux (no one mentioned

Touch of Evil in this context, but assumedly he would approve of that bit of meddling, since it conformed to Welles’ original vision of the film). “If you’re going to revisit these films, you should at least include the originals on the DVD.” He told us that the music existed previously to the post-production of the film, and that the actors, at various points, could hear it prior to shooting their scenes; “knowing the wind of the music could help them set their sails at a certain angle.” (I helpfully butted in to say that Ennio Morricone’s score for

Once Upon a Time in the West also pre-existed the movie, and that the film was shot into it; Murch nodded at the non-question and politely reported it via his microphone to the rest of the auditorium.) One of the later questions involved the differences between a flatbed and a Moviola or digital editing, and Murch talked – something he also discusses in his books – about how, with an analog system, you are forced to review material, rather than just cutting directly to the scene you want; this can be a very useful process – “you keep stirring up the compost, aerating the film – things don’t get buried. Linear systems force you to go through the stuff, and you frequently discover jewels. Creativity is frequently liberated by the limitations you face.” Though he acknowledges that digital technology’s advantages outweigh the disadvantages that stem from the lack of rescanning, he feels he needs to compensate for the loss, so he now uses still photographs from scenes he is editing, mounting them on a board in front of him as he works. Discussing this led us into philosophical territory – Murch digressed into thoughts on evolution and how “culture evolves through software” – but I’m afraid his ideas became too complex for me to be able to take adequate notes.

A final discussion involved the creation of distorted digital sounds – Murch’s invention at the time. Digital technology was a “hot topic” in the early 1970’s, and Murch presumed that if Harry could actually edit out the waveforms of the band playing in Union Square and so forth, it would have to be done digitally. Murch had never heard a digital recording at that point, let alone a digital distortion, but he realized that to do justice to Harry’s technology – the device on the rolled up blueprints that Moran is hot to get a look at – and make the scenes believable, the distortions would have to be digital. He used an

ARP synthesizer, and filtered voices through it to produce the distortions that you hear in the film. (Apparently

THX 1138’s later digital distortions were done by broadcasting recordings of voices over radio and setting the channel slightly off).

After a round of applause, Murch waited at the front to sign books, and I was first in line for that, too. I’d already bought a signed copy of

The Conversations at the “merch” – get it? – table out front, but I had important business to attend to. My friend Dan Kibke, a local musician and audio technophile who has done much to stimulate my interest in Murch, had been unable to get in – he arrived too late, was about the twentieth person in the lineup, and was not rude enough to successfully butt ahead of the SFU student who’d bitched at such length about the cold. He passed on his copy of

In the Blink of an Eye for me to get signed. I had the perfect inscription suggestion ready for Murch. Dan is a great fan of

THX 1138, and one of the canned voices you hear in that dystopian vision repeatedly asks the unhappily sedated consumers and workers, “What’s wrong?” Dan is fond of riffing on this line in conversation, so I briefly explained this to Mr. Murch and asked him if he could sign the book, “To Dan – ‘what’s wrong?’ – Walter Murch.”

I liked Murch a lot for his smirk as he proceeded to do this.